Written by Dr. Eric Caparulo, Director of The Craig High School

What do all parents and their teens have in common besides sharing last names and addresses? Surprisingly, it's high school. It is something that we have all experienced, yet each of us might define it a little differently. As adults, we have our own perceptions of what the high school experience was to us and what we walked out the doors with after our four-year secondary adventures. Some might say it was just a diploma, others the memory of a sports team and glory on the field, and still others would say it was just a springboard to college. One thing we would all say is that we wrapped up our high school careers with aspirations and hopes that we were ready to take on whatever the world had in store for us after graduation.

High school is an experience that we hope is both positive and fulfilling for our teens, that it prepares them for their next steps and lays a foundation for them to achieve academic and personal success. Based on that hope, high school needs to prioritize guiding our teens to not only becoming the independent learners that we as parents and educators know that they can be but, just as importantly, they need to also guide them in developing a strong sense of self.

At The Craig School - High School, becoming an independent learner and strengthening one’s sense of self go hand in hand. For all teens, it is essential for success, but for teens with learning disabilities, it is even more so. Those with learning disabilities spend a significant amount of time during their early school years learning what they can’t do well, and in too many cases, those students start to define themselves by their learning disability. That is why at The Craig School - High School, we not only focus on guiding our students to become independent learners but also on developing that essential sense of self.

We accomplish this through a series of courses that make up our Self Program, a program that teaches our students that their learning disability is just a piece of the puzzle that makes them who they are. It will always be a part of them, but they are so much more. As freshmen, they start with Self and Group Dynamics led by our school psychologist where they learn about their learning styles, multiple intelligences, and their individual aptitudes, and how they connect to their success both in and out of the classroom. They also learn about their specific learning disabilities, individualized accommodations, and the focused, individualized strategies that allow them to manage their learning disabilities academically and socially.

The elements from the Self and Group Dynamics course then carry over into their Sophomore Career Awareness course, where they apply these aptitudes and multiple intelligences to the potentials of various career fields. They create their first student resume, explore the workplace, hear from experts in various career fields and prepare for job interviews.

Next comes Post-Secondary Exploration, where students apply all of their self- awareness garnered from the other Self Courses and begin to see the potential of post-secondary possibilities. Our Juniors learn about the college process with our Director of College Counseling, with a specific focus on support and accommodations. Students have an active role in the exploration of specific post- secondary schools and programs that meet their individualized criteria and further support their aptitudes and potential future aspirations.

Our Self Program wraps up with Life After High School, a course that lives up to its name. Students explore campus life, the idea of having a roommate, and what it means to truly be independent and accountable. They hear from recent grads who offer a current picture of life after high school through the lens of a fellow classmate who has learning disabilities.

When teenagers begin their high school adventures, they are closer to adulthood than at any other point in their lives. They are expected in the next four years to walk down that graduation aisle knowing who they are and what comes next. As educators and parents who have shared that high school experience and those same expectations bestowed upon us, we know the challenges that our teens will encounter. The higher their self-esteem, the greater their self-awareness

(learning disabilities and aptitudes), the willingness to embrace who they are as a whole person (self- acceptance), and their ability to pull that all together to effectively self-advocate is what we truly aspire for our teens. This sense of Self will allow our Craig High future grads to take on whatever the world has in store for them after graduation and allow us fellow high school grads, parents and educators some peace of mind, knowing that they are going to be OK.

By Jennifer Guthrie

Director of The Lower and Middle School

SEL has become a standard term in education over the last few years, but what is it really? Why has there been such a push? Is it important for a school to include SEL education? The Craig School’s mission is to provide to our students a strategy-based, comprehensive and challenging school experience that acknowledges their learning disabilities, builds on their aptitudes, and strengthens their self-awareness and self-esteem. This mission can only be fulfilled by taking the whole child into account.

SEL stands for social and emotional learning; it is the way children acquire social and emotional skills. The five widely recognized social and emotional skills are self-awareness, self-regulation, responsible decision making, relationship skills and social awareness. These skills are developmental in nature, just like motor and language skills. Their development starts at birth and continues to evolve throughout life. Many of these skills develop naturally for many children. However, if these skills are not mastered, behavior problems can develop that can interfere with their functioning in school and their ability to learn. Students with learning disabilities often have delayed executive functioning skills including self-control and self-regulation, which are directly related to their social and emotional skills. Recent years have led to an increase in this delay.

Before, during and after the pandemic, many adults, in and out of the education world were rightly concerned about the academic losses our children were suffering. There was little if any discussion around the loss of social and emotional skill development. When a skill is not used or practiced, it is lost and needs to be relearned. For developing children, these skills are much more important, and take much more time to relearn.

Our children’s social and emotional development stagnated during the pandemic. Even those, like students at The Craig School, who were in person during the 2021-22 school year, remained 6 feet apart and were not allowed to work with partners or small groups. They did not practice or develop their social-emotional skills. We noticed students who did not understand personal boundaries and were invading another’s “bubble”. While completing work with partners or playing on the playground, they needed adult help to compromise on what to choose. We also had an increase of students seeking support because a classmate was bothering them by making noises or moving too much. As a school, we found that we needed to do more to help our students gain some of the ground they lost and give them time to practice and develop these skills.

We have and continue to add pieces to our program to help our students develop their social and emotional skills. Our well-developed, scaffolded school-wide executive functioning program allows students to recognize and build their EF skills. School-wide SEL themes are directly taught and then woven throughout their day, the first of which is self-awareness. The Craig Lower and Middle School are adopting the Zones of Regulation, a research-based program aimed at increasing self-awareness and self-regulation. In addition, scheduled SEL classes across all divisions are times dedicated to direct instruction and real-time practice of these skills.

A very important layer to this system is the social clinicians at each division who support the teachers and students. All of The Craig School students have access to their social clinician to guide them through peer mediation, social stressors or personal goals. Students are welcome to meet with their clinician on an as-needed basis.

Every aspect of our program, including our approach to SEL instruction, is specially planned and executed for those with language-based learning disabilities. The whole school to small group to individual layered system of support provides the structure, repetition and immersive environment for our students to not only access their curriculum, but also to learn and thrive.

“[Students with dyslexia]...think differently. They are intuitive and excel at problem solving, seeing the big picture, and simplifying. They feast on visualizing, abstract thinking, and thinking out of the box. They are…inspired visionaries” (Shaywitz, 2003).

These words from Dr. Sally Shaywitz, Co-Founder and Co-Director of the Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity and author of Overcoming Dyslexia speak to the unique strengths that many students with language-based learning differences possess. Adding on to her strengths profile is keen spatial reasoning, that is, the ability to think about and manipulate objects in three dimensions, which, like the above attributes, are uniquely suited for STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) pursuits. I believe that it is in the very nature of being “wired differently” that a learning profile compatible with the cognitive demands of STEM emerges. What is unfortunate, however, is that in traditional classrooms, students with language-based learning differences may be left out of STEM learning mainly due to assessment structures, such as language-dependent tests, and instructional approaches which lean heavily on language processing and symbolic decoding skills. The cognitive processing burden this creates impacts a student’s ability to truly demonstrate their learning and mastery of the subject; it also perpetuates barriers to meaningful learning for students with exceptionalities. These traditional school structures then may lead to being excluded from more advanced-level STEM courses and future career opportunities. STEM-based education is important for all learners, providing opportunities for developing 21st-century skills integral to the fabric of today’s workforce.

STEM-based education far surpasses concepts in math and science as it is keenly focused on hands-on learning with real-world applications through a cross-curricular lens, all while developing creativity, collaboration, communication, and flexibility, for example. There are many benefits of STEM education beyond scientific literacy; here are just a few:

At The Craig School, we speak often about our goal to foster independent learners. Part of this process requires a closer examination of our students’ needs and the compensatory strategies, interventions, or instructional strategies central to creating an environment conducive to their most optimal growth. This week, I turn our attention to working memory and its role in learning. In short, working memory is the small amount of information that is held in the mind while simultaneously understood and used. It has auditory or verbal components best described as a sort of recording of what you hear containing words, numbers, and sentences, and visual-spatial elements described as a visual representation of information in the “mind’s eye” (images, pictures, and information about location in space).

Working memory impacts reading, information processing, problem-solving, remembering instructions, and attention. Each is important in our students’ journey as scholars. For example, word problems in math can be challenging because students must attend to clue words for operations, clue words for numbers, as well as clue words for sequencing or ordering of events all at the same time. Specific to reading, working memory provides a link to information held in long-term semantic memory stores with the meaning and pronunciation of words. Working memory impacts spelling, written expression, reading comprehension, and even fluency or automaticity. When I think about our students who struggle with working memory, I imagine them trying to hold onto incoming information while also using that same information for a task, each action taxing their cognitive load and leaving less space for the actual learning process to occur. This may be cognitively and sometimes physically exhausting for students.

Even more important than understanding working memory, is translating this understanding into actionable practice in the classroom to more effectively support our students’ learning. Faculty at The Craig School incorporate the following to support students with their working memory demands:

teaching students how to use and when to use reference sheets, memory aids, and graphic organizers,

keeping directions concise and clear as well as repeating directions,

breaking tasks into smaller chunks,

providing information through multiple means: speak it, show it, and model it method,

applying visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and tactile instructional modalities to engage learning,

increasing the meaningfulness of the material by providing examples students can relate to, and

developing routines in classroom procedures, like routines for turning in completed work, which then after repeated practice, begins to internalize and automatize, thus reducing the cognitive load demand.

While this list is not exhaustive, it does provide a glimpse into how thoughtfully and intentionally, we approach our work with your students. Please know, there are many things parents and teachers can do to understand and support our students’ working memory. As you get to know what we call “The Craig School Toolbox” you will notice commonalities in classroom settings such as highly structured and well-organized classroom environments, direct, explicit instruction, along with specific instructional practices, for example, cueing, the use of checklists, reference sheets, and reminder systems, among many other strategies. There are even things that parents can do at home, that are appropriate for our young and our old students alike, such as only giving one task command at a time, rather than a string of instructions and using verbal and visual cues to build consistent home routines, think post-it note reminders or asking your child to verbally repeat the task aloud (Child Mind Institute). While this is just a snapshot of our educational approach through the lens of one specific challenge many of our students face, I encourage continued conversation on how we can partner to best meet the needs of our students. I appreciate time spent with you in partnership and support of fostering our students’ best selves.

Introduction & Rationale

Background

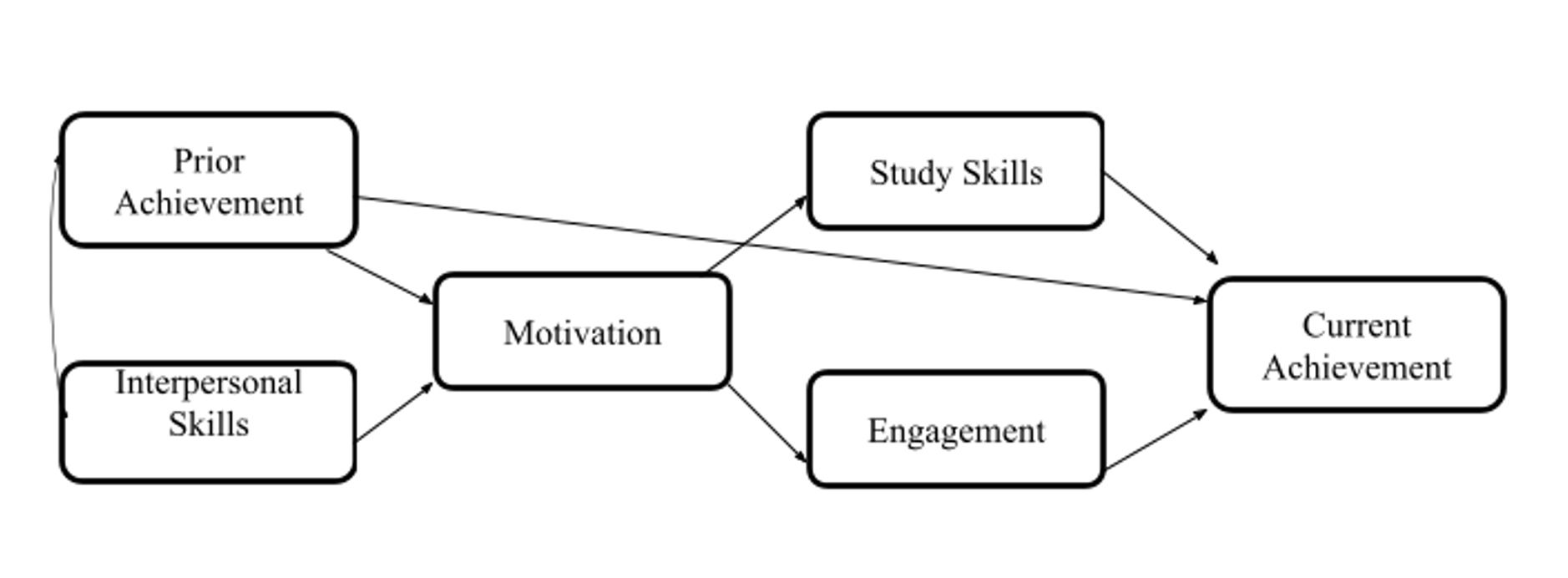

Teens with ADHD experience greater levels of academic impairment than students without ADHD. Academic enablers, non-cognitive skills and behaviors, like study skills, engagement, motivation, and interpersonal skills are essential components to optimal academic attainment. For students with ADHD, these skills tend to be underdeveloped. This study explored the attitudes, thoughts, and perspectives of students in high school diagnosed with ADHD in regards to their challenges, their strengths, and their experiences as students. As children gain more autonomy, listening to their voice is an important step on their path to self-advocacy. To inform the understanding and development of models for effective intervention that are accepted and readily adopted by teenagers with ADHD, interviews conducted with 16 students examined academic enablers from their perspective. Results from these interviews create an authentic context for exploring student perspectives about (a) the social self, the student learner in relation to teachers and peers, and (b) the individual self, and (c) the student’s use of self-regulation, self-management, and self-expression as they become more autonomous individuals with increased responsibilities for their own learning. This study examines high school students’ experiences and perspectives of their ability to learn and experiences in the classroom, the interventions teachers have taken with them, exposure to stigmatization, engagement in student agency, diagnostic labeling effects, and their self-concept (Owens & Jackson, 2017; Wiener & Daniels, 2016).

Need for Study

Persisting into adolescence and adulthood, educational impairment impacts 50 to 80% of youth with ADHD (DuPaul, Stoner, & Reid, 2014). Critical skills for students in secondary schools include the ability to engage executive functions and self-regulatory behaviors, such as planning and organization, all predictive of future academic attainment (Barkley, 1997; Volpe et al., 2006).

A large body of research exists exploring the role of behavior in academic attainment for elementary students as well as students in college. However, the cannon of literature exploring the experiences of teenagers with ADHD in relation to their acquisition of academic enablers leading to educational attainment as they navigate more autonomy, less parent, teacher, and school supports and structures, and increased independence are scant (Bolic Baric, Hellberg, Kjellberg & Hemmingsson, 2016; DiPerna, 2006; Kent et al., 2011; Wiener & Daniels, 2016; Wu & Gau, 2013).

Research shows that teenagers may be resistant to academic supports they view as stigmatizing or labeling (Bussing et al., 2016; Owens & Jackson, 2017). To inform understanding and development of models for effective intervention that are accepted and readily adopted by teenagers with ADHD, a closer look at academic enablers from their position is essential (Wei, Yu & Shaver, 2014).

Research Questions

Methods

Interview Questions

Emergent Themes

Individualized/Modulated Pacing

“So like, I also like individualized learning. So like, here, it's amazing because like, there's smaller class size and then there's also study hall that you can go to. And I really like that because then you get more time with the teacher individually. So I like it, I like when I know that I can have help individually.”

-JA, 12th grade

Teacher Directed Learning and Attention

“I'm a very, I learned by talking through things and or doing them. If a teacher is willing to talk with me about the subject, not not particularly be very restrictive on it. My brain has a very odd way of making connections. So a lot of the times if a teacher is willing to go with me on one of my weird metaphors I'll understand the subject...it just...it helps me to talk it out and say, Okay, well, it's like this and this, right? And if they say yes, then that's great. If it's no, then it's another try. And I've always found that the best way for me to learn.”

-OL, 12th grade

“And so we wrote it all down, and then we put how much time I think it's going to take, so that helped with my organization, because then that actually, it actually worked because I spent a certain amount of time on each thing and I got it done. So, she's, she's amazing with that. She's really great at organization.”

-SB, 11th grade

Passive Peer Mentoring

“Yeah, because I know that other people are you know, more focused and can do things faster. So if I have …it's sort of like cross country running, if I have someone who can pace myself. Then I can, I work a lot better.”

-FP, 10th grade

“...not doing it in my room. I just can’t concentrate. I need someone kind of there, to, like help me. Like, it’s weird. If someone’s like sitting next to me while I’m doing work, I’m doing it much better than when I am by myself.”

-KS, 10th grade

Self-Concept: Identity

“When I was a lot younger, my mom went to multiple doctors and asked them if I was autistic. And, you know, so on and so forth. There were quite a few different diagnoses that came up over the years. So, needless to say, the ADHD wasn't really a new thing for me to be diagnosed as…And parenting is hard. And when you can't find an answer for why your child is behaving like this, or why your child isn't behaving like this. It can be scary, which I understand. And I also have to know that that wasn't the correct behavior that, you know, they should have been a little more considerate.”

-OL, 12th grade

Self-Concept: Belonging

“I felt like I was different from everyone else…That was when I was first diagnosed. But then, like, as I learned more about ADHD, I’m like, no, I’m no different. I just have this thing….that kind of makes it harder for me to learn and focus.”

-JA, 12th grade

Self-Management

“Because in order to keep myself physically organized, I have to keep myself mentally organized. So like to have like to have it all organized. I try to stay on top of it, if not ahead of what's going on. Not only because I really don't like doing homework outside of the school hours, but also because when I do homework outside of school hours, it's kind of like, I get more distracted and more like, oh, I don't want to do this.”

-SS, 11th grade

Self-Awareness

“I been very good about adapting and knowing exactly what I need when I need it. Because otherwise, I’m just not going to succeed.”

-OL, 12th grade

Attention/Focus

“I'll be talking and all of a sudden, my mind just goes faster than I'm talking. I'm just like…I start fumbling on words. I'm like, I have to chill for a second. I can't talk right now. Because my mind is already like, 10 words of head of what I was already saying…”

-KS, 12h grade

Self-Expression

“I like to do whatever I can get my hands on, basically. I will do anything I can. Like, I can do fashion design. I can sing songs. And I’m learning to write songs. I’m just great at painting. I’m great at a lot of things.”

-KQ, 9th grade

Conclusions

Results from the study revealed the challenges that teenagers with ADHD face along with their perspectives on identity, self-expression, and sense of belongingness. Balancing teacher-led scaffolding and collaborative learning opportunities with peers may be one means to address the interplay of dependence moving to independence as a learner. As students mature, their responsibilities are expected to increase. However, these 16 participant interviews and observations indicate there are varying levels of student readiness to move in the direction of self-agency and autonomy. Many teens continue to need support with basic study skills like organization, prioritization, planning, and time management. Additionally, engaging the student in work that is meaningful to them gives them a greater sense of ownership over the process of learning, and increases their ability to attend to the task. Teachers who give students choice in the type of task (e.g. essay instead of multiple choice test, or project rather than worksheet) are able to leverage the students’ buy-in and innate motivation to get the work done. Teachers are encouraged to allow the students to use multiple means to represent their learning, encouraging the student to tap into their affinity for self-expression. Finally, increasing relevant pre-service training for teachers would not only benefit students with ADHD, but all learners so that teachers are equipped with a toolbox of instructional strategies and interventions that far exceed the traditional needs in the high school classroom.

Throughout the year, I have written about strengths-based education for students with exceptionalities, the importance of developing a strong sense of self-efficacy and creating safe, nurturing, positive spaces for learning. Each is related to the broader educational implications of our mindset around disability. Something I think about often is how schools would function if rather than viewing learning disabilities, as deficits, we viewed them as part of the natural variations of the human genome? Sometimes called the social model of disability, the person-environment-fit, or even the neurodiversity model, this view holds that dyslexia or specific learning disability, for example, is merely but one component of identity and functioning, not its totality, and is best defined as the “gap between a person’s capacities and the demands of the environment” (Wehmeyer, 2020). An example of this framework is a student who struggles with reading and is presented only with print curricular resources. By providing one means to access the curriculum the student is hampered in how much they are able to learn. However, this same student, presented with speech-to-text technology or audiobooks now has access to learn more substantially. The person is still the same, the environment shifted.

By moving our thinking from disability as a deficit or something needing to be fixed or cured to a model built more on capacity-building and environmental changes to support learning, a student’s educational experiences are enhanced and their strengths are leveraged for deeper learning and meaning-making. Students benefit from teachers who provide multiple means of representation, multiple means of expression and action, and multiple means of engagement to meet their students’ individual needs. A simple example is the use of a graphic organizer with reduced text to bridge the gap between challenges with reading comprehension and the student’s ability to recall information in an ordered sequence. Fundamental competencies, such as literacy skills like inference making at the paragraph level, are not ignored but addressed. Couple that foundational work with multiple access points to curriculum that matches the increased demands of literacy throughout the school years and the needs of the individual and we have lessened the gap between ability and environment. Daily, The Craig School balances the educational needs of our students by providing ample instructional time for addressing their greatest needs while also supporting the development of strengths, all the while recognizing that our students are fully human, ever-evolving, and full of ability.

Within this new mindset, the language we use and the labels we attach to differences are also important factors to consider. A glance at the above two paragraphs highlights the use of the word “disability” as a common descriptor. We function in a world where to get the supports and services that our students need, they are “classified” and this happens after identification of a disorder or disability. This practice of labeling inherently impacts how one thinks of themself and how one is perceived by others. In turn, educational decisions regarding when students are “ready” to learn and in what ways they are capable of learning follow.

What I am so proud of at The Craig School is that we cultivate and support our students’ positive identities as learners. We partner with you to build their capacity through targeted, personalized learning experiences that remove barriers to learning. Finally, we design the broader curriculum to allow for greater access and participation from each of our students. Our students recognize they are capable of so much more than the limiting beliefs they may have once experienced.

I leave you with this powerful statement of truth-telling from Rapport-Schlichtmann, Boucher, and Evans (2018) that applies to all disability types:

The challenges of dyslexia are real, but they are limiting only to the extent that we allow them to be. The moment we start defining a person by deficits, we undermine their capacity to be successful, and there is no space to develop strengths and positively adapt. If we instead build the capacity of students with dyslexia to improve on their areas of weakness, as well as build on their individual and unique areas of strength, we begin to create the foundation for thriving in learning and life.

Speaking with a language-arts teacher in our lower and middle school, I was reminded of the importance of responsive and student-focused teaching and learning. She spoke about tapping into students’ interests, watching for how students are connecting to their learning, and finding meaningful moments for cross-curricular teaching all while sharing the bigger picture of learning. I could see her light up when sharing her experiences integrating a moment for applied math into a reading fluency activity and helping a student approach a math challenge from a new perspective by playing a game to learn basic math facts during Homework Help. For me, what was exciting, was to listen to a teacher sharing in practical ways the value she places on teacher-student relationships and on respecting and integrating students’ perspectives into her teaching so that she may better understand their needs, preferences, goals, and areas of resistance.

Through an education theory lens, her actions are hallmarks of a student-directed learning approach called, autonomy-supported learning. This is best described as an instructional practice that leans on flexible, reciprocal, positive, and healthy teacher-student relationships and classroom environments to promote student engagement and intrinsic motivation. Just as I wrote last week about teacher-directed learning, like explicit instruction, student-directed learning is equally important to encourage and foster. As my dear friend and retired special education teacher, Steve Horner, once commented to me, “There must be a balanced approach to learning; a balanced person should be the goal. There are times that the student must take control and direct their own learning, the teacher then becomes the facilitator and only intervenes when learning ceases [or] frustration overtakes the student.” We understand that with the constraints of curricular standards and goals, it is not possible to give students full voice and choice in what they learn and how they learn it. However, as educators, we can foster more independent learning and curiosity by tuning into, respecting, and integrating student perspectives into our teaching, just like the example of our language arts teacher above. By doing so we increase student autonomy which then lends itself to boosting the intrinsic motivation of our students. The end result, are students who are more fully engaged at school, who feel more connected to their teachers, and who feel a sense of belonging.

Dr. Kara A Loftin

Over the past decade or so, a divide has widened in educational circles over the impact of teacher-directed versus student-directed learning based on the idea that teacher-directed learning is passive, rather than active and engaged learning, and therefore, not as effective for student achievement and learning. However, viewing the two approaches as distinct and separate is misguided. The instructional strategies representative of these dual approaches, such as differentiated learning (student-directed) and explicit instruction (teacher-directed) are most effective when paired together. This week, let’s take a closer look at explicit instruction, a practice you most likely have heard about during parent-teacher conferences or IEP/ISP meetings.

An instructional approach woven throughout all disciplines and grades at The Craig School is direct, explicit, systematic instruction (explicit instruction). Explicit instruction is a teacher-directed approach to learning that is steeped in decades of empirical research indicating its effectiveness for students with exceptionalities, in particular students with learning differences. It is structured, sequential, and designed to build on previous learning. A good example is learning to read. First, students learn letter-sound relationships. This knowledge then leads to linking sounds together (phonemes) and knowing the symbols that represent them (graphemes). Teachers decide when to introduce each letter-sound relationship and use modeling to make sure students can accurately pronounce each sound. This structured and sequential approach in explicit instruction starts with identifying clear learning goals and objectives, followed by the purposeful organization of lessons, reviewing instructions so that student expectations are known, modeling, verbalizing the thinking process, providing opportunities to practice, asking questions for understanding, and giving timely feedback. Mastering concepts is incremental. Generalization to new contexts happens gradually. Finally, teacher guidance is reduced.

Why use this high leverage practice? Simple, it works! Explicit instruction provides a path for your child to learn to their potential. It is a research-based, effective means to teach students with exceptionalities. Unlike what some may think of as a limiting and dependency promoting instructional practice, explicit instruction makes higher-order thinking, inquiry-based, and other forms of student-directed learning more accessible. It engages students, teaches them the process of learning, and helps build decision-making and social skills. Furthermore, for students who struggle with working memory, explicit instruction reduces the load on working memory. By freeing up some of the required working memory, we free up cognitive resources for the learning itself. Finally, it provides a means for students who may struggle with attention to tune into the most important information at each step along the way. Explicit instruction works in schools and it also works at home. I’ll leave you with one home example: helping your child learn to make their bed. Break down this task into smaller parts: 1. Strip sheets, blankets, and pillowcases. 2. Put blankets and pillows on the table, 3. Get sheets and pillowcases from the closet, and so forth. Model the steps and provide clear expectations, verbalize the thinking process, provide lots of constructive, timely feedback, and practice, practice, practice.

Foundational grade-level skills and concepts, along with key 21st-century skills like collaboration, communication, and critical thinking are improved greatly through explicit instruction. Pair that with differentiated instructional approaches and our students are given the best opportunities for success both now and into the future.

If you have emailed me, you may have noticed my email signature line quote that reads, “When a flower doesn’t bloom, you fix the environment in which it grows, not the flower” (Alexander den Heijer). This one phrase perfectly sums up my educational philosophy. As an educator, I believe that children are beautiful, whole, and perfect beings. They are messy, they are works in progress, and they represent the wonder of possibility. I believe that it is not the child that needs to be somehow “fixed,” rather, that when our children are given the right opportunities, support, kindness, and genuine care, they begin to blossom, they begin to move more fully into their potential.

As an educator, I find myself immersed in the “how” and the “what” of the education of young minds. For example, how do we increase academic engagement for students with learning disabilities, and what instructional practices will best suit the students’ unique learning needs? Sometimes the “why” is more nebulous. Why do we do what we do? I believe that in order to truly be successful, we must more fully understand our “why.” This is true for me as an educator and is just as important for The Craig School community to understand.

A school’s mission statement and core values drive the “why” of the community. These form the basis for our decisions. I would argue that the most successful schools are, at their core, mission-driven, and purpose-focused. Just like the beacon atop a lighthouse illuminates a path in the midst of the unknown, our mission and values guide decisions both great and small. As I begin a new chapter as the Head of School at The Craig School it is of utmost importance that together, we are reminded of our shared “why.”

At The Craig School we acknowledge learning differences, we understand them, and we provide the instructional strategies and supports that allow the student to grow and learn. We believe in a firm foundation of academic knowledge and higher-order thinking skills; we believe in whole child development and that social, emotional, and moral growth are integral to a student’s education; we believe that with the right environment and opportunities that all students can and will thrive. Our mission is focused on a strategy-based, comprehensive, and challenging education that is designed for the unique academic needs of students with learning disabilities while also celebrating and bringing out each students’ aptitudes and strengths. To this end, fostering a child’s self-esteem and self-awareness is paramount.

I encourage you to take a moment to read through the Statement of Core Values of The Craig School and the Mission Statement of The Craig School. These are our collective “whys.” May they provide for you a light and a path forward as we work hand in hand to nurture the true potential and abilities of all of our students.

Learning Ally. Kahoot. Kami. IXL. Read & Write. Mindomo. You may have heard your child talking about, searching for, or even using one of these learning tools, some of which are instructional software (Kahoot, IXL, Mindomo) and others are known as Assistive Technology (Learning Ally, Kami, Read & Write). Assistive technology (AT) is any item, piece of equipment, system, or device that increases, maintains, or improves a student’s ability to learn, whereas instructional software does not remove barriers to learning, but rather is used as a teaching tool for academic skills or content. COVID-19 has brought with it change to the field of education. One of the positive outcomes educators are experiencing is a renewed focus on innovative and collaborative pedagogies and the opportunity to take a closer look at the efficacy of the interventions, curriculum, and programs within a school. In our current hybrid model, where learning takes place synchronously in a physical school environment and through a virtual platform, our use of technology to enhance learning and reduce barriers continues to be a powerful tool in our teacher’s tool belt. I have had a few parents ask about the use of technology in the classroom. Here is a snapshot of the most commonly used assistive technology and educational software your child may experience at The Craig School:

Assistive Technology

Kami: Kami is an app that converts documents to PDF files. While this seems simple on the surface, its real strength is its use as a support for critical reading by allowing teachers to guide and comment on students’ annotations and by providing a platform for students to interact with text and to make meaningful connections among multiple texts.

Learning Ally: Learning Ally is a digital library of human-read audiobooks, which include everything from classic literature to standard textbooks. Features include highlighted text synced with audio narration, speed control, bookmarking, highlighting, and note-taking.

Read & Write: Read & Write is a literacy tool featuring text-to-speech options that support listening comprehension through engaging both auditory and visual senses, talk & type feature where students can take notes and record observations orally, highlighter option to support note-taking, and a word prediction tool to help develop writing skills, among other features.

Educational Software

IXL: At The Craig School, IXL math and IXL language arts is used. Students are given questions on a specific standard in a core subject. When students successfully answer questions, they advance through the standard and the problems presented adapt in real-time to where they are in mastering the concept. It is a flexible tool used for mastery-based learning.

Kahoot!: Gamification of learning is a trend in education and Kahoot is a useful tool toward that end. This app provides a platform for students or teachers to create, share, and play learning games or trivia quizzes.

Mindomo: Mindomo is an app used for mind mapping. Mind mapping is a learning tool that helps students master concepts through generating new ideas, synthesizing and structuring information, problem-solving, decision making, using evidence to support claims, and accurate planning.

For more information on ways of giving or to make a donation online you can clicking here.