Written by Dr. Eric Caparulo, Director of The Craig High School

What do all parents and their teens have in common besides sharing last names and addresses? Surprisingly, it's high school. It is something that we have all experienced, yet each of us might define it a little differently. As adults, we have our own perceptions of what the high school experience was to us and what we walked out the doors with after our four-year secondary adventures. Some might say it was just a diploma, others the memory of a sports team and glory on the field, and still others would say it was just a springboard to college. One thing we would all say is that we wrapped up our high school careers with aspirations and hopes that we were ready to take on whatever the world had in store for us after graduation.

High school is an experience that we hope is both positive and fulfilling for our teens, that it prepares them for their next steps and lays a foundation for them to achieve academic and personal success. Based on that hope, high school needs to prioritize guiding our teens to not only becoming the independent learners that we as parents and educators know that they can be but, just as importantly, they need to also guide them in developing a strong sense of self.

At The Craig School - High School, becoming an independent learner and strengthening one’s sense of self go hand in hand. For all teens, it is essential for success, but for teens with learning disabilities, it is even more so. Those with learning disabilities spend a significant amount of time during their early school years learning what they can’t do well, and in too many cases, those students start to define themselves by their learning disability. That is why at The Craig School - High School, we not only focus on guiding our students to become independent learners but also on developing that essential sense of self.

We accomplish this through a series of courses that make up our Self Program, a program that teaches our students that their learning disability is just a piece of the puzzle that makes them who they are. It will always be a part of them, but they are so much more. As freshmen, they start with Self and Group Dynamics led by our school psychologist where they learn about their learning styles, multiple intelligences, and their individual aptitudes, and how they connect to their success both in and out of the classroom. They also learn about their specific learning disabilities, individualized accommodations, and the focused, individualized strategies that allow them to manage their learning disabilities academically and socially.

The elements from the Self and Group Dynamics course then carry over into their Sophomore Career Awareness course, where they apply these aptitudes and multiple intelligences to the potentials of various career fields. They create their first student resume, explore the workplace, hear from experts in various career fields and prepare for job interviews.

Next comes Post-Secondary Exploration, where students apply all of their self- awareness garnered from the other Self Courses and begin to see the potential of post-secondary possibilities. Our Juniors learn about the college process with our Director of College Counseling, with a specific focus on support and accommodations. Students have an active role in the exploration of specific post- secondary schools and programs that meet their individualized criteria and further support their aptitudes and potential future aspirations.

Our Self Program wraps up with Life After High School, a course that lives up to its name. Students explore campus life, the idea of having a roommate, and what it means to truly be independent and accountable. They hear from recent grads who offer a current picture of life after high school through the lens of a fellow classmate who has learning disabilities.

When teenagers begin their high school adventures, they are closer to adulthood than at any other point in their lives. They are expected in the next four years to walk down that graduation aisle knowing who they are and what comes next. As educators and parents who have shared that high school experience and those same expectations bestowed upon us, we know the challenges that our teens will encounter. The higher their self-esteem, the greater their self-awareness

(learning disabilities and aptitudes), the willingness to embrace who they are as a whole person (self- acceptance), and their ability to pull that all together to effectively self-advocate is what we truly aspire for our teens. This sense of Self will allow our Craig High future grads to take on whatever the world has in store for them after graduation and allow us fellow high school grads, parents and educators some peace of mind, knowing that they are going to be OK.

By Jennifer Guthrie

Director of The Lower and Middle School

SEL has become a standard term in education over the last few years, but what is it really? Why has there been such a push? Is it important for a school to include SEL education? The Craig School’s mission is to provide to our students a strategy-based, comprehensive and challenging school experience that acknowledges their learning disabilities, builds on their aptitudes, and strengthens their self-awareness and self-esteem. This mission can only be fulfilled by taking the whole child into account.

SEL stands for social and emotional learning; it is the way children acquire social and emotional skills. The five widely recognized social and emotional skills are self-awareness, self-regulation, responsible decision making, relationship skills and social awareness. These skills are developmental in nature, just like motor and language skills. Their development starts at birth and continues to evolve throughout life. Many of these skills develop naturally for many children. However, if these skills are not mastered, behavior problems can develop that can interfere with their functioning in school and their ability to learn. Students with learning disabilities often have delayed executive functioning skills including self-control and self-regulation, which are directly related to their social and emotional skills. Recent years have led to an increase in this delay.

Before, during and after the pandemic, many adults, in and out of the education world were rightly concerned about the academic losses our children were suffering. There was little if any discussion around the loss of social and emotional skill development. When a skill is not used or practiced, it is lost and needs to be relearned. For developing children, these skills are much more important, and take much more time to relearn.

Our children’s social and emotional development stagnated during the pandemic. Even those, like students at The Craig School, who were in person during the 2021-22 school year, remained 6 feet apart and were not allowed to work with partners or small groups. They did not practice or develop their social-emotional skills. We noticed students who did not understand personal boundaries and were invading another’s “bubble”. While completing work with partners or playing on the playground, they needed adult help to compromise on what to choose. We also had an increase of students seeking support because a classmate was bothering them by making noises or moving too much. As a school, we found that we needed to do more to help our students gain some of the ground they lost and give them time to practice and develop these skills.

We have and continue to add pieces to our program to help our students develop their social and emotional skills. Our well-developed, scaffolded school-wide executive functioning program allows students to recognize and build their EF skills. School-wide SEL themes are directly taught and then woven throughout their day, the first of which is self-awareness. The Craig Lower and Middle School are adopting the Zones of Regulation, a research-based program aimed at increasing self-awareness and self-regulation. In addition, scheduled SEL classes across all divisions are times dedicated to direct instruction and real-time practice of these skills.

A very important layer to this system is the social clinicians at each division who support the teachers and students. All of The Craig School students have access to their social clinician to guide them through peer mediation, social stressors or personal goals. Students are welcome to meet with their clinician on an as-needed basis.

Every aspect of our program, including our approach to SEL instruction, is specially planned and executed for those with language-based learning disabilities. The whole school to small group to individual layered system of support provides the structure, repetition and immersive environment for our students to not only access their curriculum, but also to learn and thrive.

At Craig High School, a specialized college prep program for high school students with learning disabilities, students learn executive functioning skills and are immersed in cross-curricular strategic approaches that allow them to manage their learning and ultimately become the independent learners they are capable of and will need to be to navigate the post-secondary world.

At Craig High School, a specialized college prep program for high school students with learning disabilities, students learn executive functioning skills and are immersed in cross-curricular strategic approaches that allow them to manage their learning and ultimately become the independent learners they are capable of and will need to be to navigate the post-secondary world.

By Dr. Eric Caparulo

Director of Craig High School

As the director of The Craig High School for the past 23 years, one of the most common questions that I am asked is, “What makes Craig High different than any other high school?” My response is to share who we are: Craig High is a specialized college prep program for high school students with learning disabilities.

Each element of our identity is essential in defining who we are as a school and community. We are a college prep program with the goal of preparing our students for whatever post-secondary opportunities await them. This preparation involves building executive functioning skills and immersion in cross-curricular strategic approaches that allow our students to manage their learning and ultimately become the independent learners they are capable of and will need to be to navigate the post-secondary world.

We are an independent high school that exceeds New Jersey graduation requirements and that provides to our students what we, as educators and parents, aspire for all of our teens — a comprehensive high school experience. This experience includes more than just academics. It includes sports teams, student-led clubs, student councils, National Honor and Art Societies, proms, Spirit Days and Stepping Outs (our version of afterschool adventures).

The most defining principle of who we are is that we are specialists in working with students with learning disabilities. There is a reason that the term “learning disability” is at the tail end of our school identity. It is because learning disabilities are a commonality of the students of Craig High, but it does not define them as individuals. It is an essential piece of their self-puzzle and one that they must come to terms with, accept and learn to manage. That is where Craig High comes in. As important as any academic skill or strategic research-based approach is, so too is our students’ sense of self and the understanding that their disability is just a piece of who they are. They have aptitudes, passions, drives and motivations that they must learn to embrace and navigate to truly understand the self-puzzle that makes them who they are as both young adults and scholars. That is what makes The Craig High School unique and different from traditional high schools.

Dear Community,

Continuing our series spotlighting Dyslexia Awareness Month, one strength of our dyslexic learners is highlighted today, visuospatial awareness. Beginning with the work of Dr. Samuel T. Orton (1925), to neurologist Noman Geschwind (1982), to dyslexia scholars today (Eide & Eide, 2012; Shaywitz, 2016; Wolf, 2020), dyslexia has long been associated with visual-spatial strengths; strengths particularly aligned with art, music, engineering, and architecture, to name a few.

Described as a “superpower” of students with dyslexia, visuospatial awareness provides a creative advantage over neurotypical peers (Eide & Eide, 2012). Marked by non-verbal thought processes that allow for the manipulation or examination of visual images in one’s mind while seeing things from all angles, visuospatial awareness integrates both visual and spatial information quickly and efficiently, leading to innovation, creativity, and alternate ways to gather knowledge and enhance learning (Shaywitz, 2016). Visual-spatial thinking helps students find meaning in the shape, size, orientation, location, direction, or trajectory of objects and their relative positions and uses the properties of space as a vehicle for structuring problems, finding answers, and expressing solutions. Time and again, I have heard students say, “I just can see it differently,” when asked about a particularly novel approach to problem-solving they came up with. The capacity to “see” things differently points to our students’ visuospatial thinking strengths.

Parents, recognizing our students’ strengths are integral to fostering positive self-identity, and to do what our mission calls us to do, “build on [students’] aptitudes, and strengthen their self-awareness and self-esteem.” Our students’ challenges are real and there are many days when both you and your child may feel disheartened. However, our students are also full of potential with many strengths to recognize and celebrate.

Dear Community,

October is known worldwide as Dyslexia Awareness month and as such this letter highlights a particular student profile that is near and dear to my heart as I have seen over the last two and a half decades working with students who learn differently. These students frequently are overlooked in traditional schools when determining appropriate interventions and services–students who may struggle to read and write (e.g. dyslexia) while also struggling with attention and working memory (e.g. ADHD). A true testament to The Craig School is our ability to tease out our students' unique strengths and challenges to individualize a structured literacy program that best suits their needs.

Most of you may know that Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), a developmental impairment of the brain’s self-management system, and its executive functions, affects approximately 11% of school-aged children (CDC). This can present as daydreaming, absent-mindedness, fidgeting, restlessness, or a combination of these traits, among others. We also know that about 20% of school-aged children struggle with reading, writing, and spelling significantly enough to meet the diagnostic criteria for dyslexia (IDA). What is interesting is to notice where the two meet. For students diagnosed with ADHD as the primary barrier to their educational progress, anywhere between 8% and 39% have a secondary diagnosis of a reading disability.

The cognitive profile of students with co-occurring ADHD and dyslexia is unique from students with dyslexia alone as social and emotional skill deficits are present in addition to academic (phonological, orthographical, and comprehension) deficits. Many studies confirm a cognitive relationship between dyslexia and ADHD diagnoses pertaining to executive functions, which include attention, inhibition, planning, organizing, time perception, and working memory. For example, poor reading performance may be attributed to deficits in sustained attention, working memory, planning, organizing, and processing speed. Additionally, there may be a significant difference in the reading speed between those with ADHD and neuro-typical students. This may point to underlying issues concerning working memory and its role in processing speed, reading fluency, and spelling accuracy.

At The Craig School, our teachers use instructional strategies to address working memory deficits, like graphic organizers, summary strategies, and task sequencing guides. However, these tools will not address reading fluency. A structured literacy program, found at The Craig School with our extensive use of Orton-Gillingham methodology, coupled with executive function skill development allows us to better meet the needs of our students. Working memory, processing speed, and sustained attention, for example, are woven through our curriculum from second through twelfth grade. Teachers at The Craig School are immersed in evidence-based instructional practices and programs designed to bring out the best in students who learn differently and are incredibly committed to doing the hard work that is necessary to see each student reach success.

Reading comprehension provides a path for our students to identify simple facts presented in texts; make judgments or evaluate the contents of texts; and finally, connect one text to other texts or situations. Simply, reading comprehension allows our students to make meaning from what they read. Structured literacy programs, such as what we provide at The Craig School, address fluency instruction distinctly from the components of structural language that we, as parents and educators, may hear spoken of often, such as phonemes, morphemes, syntax, and semantics. Fluency, however, is much more complex than “automaticity” or decoding a word at a steady rate without any additions, substitutions, or omissions.

Reading fluency has three major components — a) accuracy, b) rate of reading and c) prosody — and each needs attention. When students can decode unfamiliar words accurately, use context to help correct errors in word reading, and have mastered several sight words, they are said to be accurate readers. Rate of reading can be defined as one’s ability to recognize words automatically or almost automatically, to read at a sufficient rate per minute, and to maintain rate or adjust rate in accordance with increasingly more difficult texts. Finally, prosody, or expression, is how the student attends to punctuation. It is a measure of phrasing, intonation, and timing, and it is the vehicle in which students express and communicate the meaning of the text.

Fluency is measured through informal and formal means, such as curriculum-based measurements (CBM) such as the Hasbrouck-Tindal Oral Reading Fluency (ORF), or a norm-referenced assessment, such as the Group Reading Assessment and Diagnostic Evaluation (GRADE), both among evaluation tools used at The Craig School. The benefit of an informal assessment is screening and progress monitoring. When used as progress monitoring tools, the extent to which the student is improving from the instruction and intervention is measured. Having a clearer picture of the student’s progress allows our reading and Orton Gillingham teachers to adjust programs and goals or to determine if they should stay the course. It allows us to be responsive to the instructional needs of our students in a thoughtful and timely manner. Norm-referenced assessments, such as the GRADE, include measures of reading comprehension, language comprehension, semantics, decoding, cipher knowledge and letter knowledge, and provide benchmarks from which to build a comprehensive, customized reading program.

Once we have a gauge of where the student is in terms of reading fluency, the instructional program shifts to the student’s specific needs so that the student begins to read with ease and can devote all of his or her attention to comprehension. For students with dyslexia, a great amount of energy is placed on decoding or word identification. Little is left for understanding what was read. Moreover, a reduced rate of reading increases subsequent challenges with comprehension. However, as Janet Cozine, longtime director of the Lower School and Middle School, noted, “Fluent reading increases comprehension, but parents, what you need to realize is if we push students to read faster than they can comprehend, it is counterproductive.” Reading and Orton Gillingham teachers engage in a delicate dance to balance all five core components of reading — phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension (National Reading Panel) — and to do so in a manner that is uniquely suited to the needs of the individual student.

Fluency takes practice and the best practice is through oral reading. You, too, should read aloud to your student as explicit modeling of fluent reading (e.g., “I do, We do, You do” method) is one of the most effective ways of improving read- ing fluency (Chard, Vaughn, & Tyler, 2002). Don’t forget the power of positive and meaningful feedback as an effective tool as well. Fluency practice applies not only to our students in the lower school but also to our middle and high school students. Teens may improve their fluency through listening to an adult read a text aloud to model fluent reading, by reading along with an audiobook, or by partner-reading when studying for an upcoming test.

By opening the door to fluency, our students explore a new world of understanding and can benefit from, and perhaps even learn to enjoy, the process of reading, resulting in high- er levels of student engagement and motivation.

Currently celebrating its 42nd anniversary, The Craig School is an independent school that specializes in working with students with language-based learning differences in grades two through 12. The Craig School’s program features proven, research-based learning strategies based on a comprehensive, whole-child approach and multisensory instructional strategies. Our tools allow students to build their academic foundations, increase their ability to be active and independent learners, and develop a sense of who they are as individuals and students. Visit us at craigschool.org.

“[Students with dyslexia]...think differently. They are intuitive and excel at problem solving, seeing the big picture, and simplifying. They feast on visualizing, abstract thinking, and thinking out of the box. They are…inspired visionaries” (Shaywitz, 2003).

These words from Dr. Sally Shaywitz, Co-Founder and Co-Director of the Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity and author of Overcoming Dyslexia speak to the unique strengths that many students with language-based learning differences possess. Adding on to her strengths profile is keen spatial reasoning, that is, the ability to think about and manipulate objects in three dimensions, which, like the above attributes, are uniquely suited for STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) pursuits. I believe that it is in the very nature of being “wired differently” that a learning profile compatible with the cognitive demands of STEM emerges. What is unfortunate, however, is that in traditional classrooms, students with language-based learning differences may be left out of STEM learning mainly due to assessment structures, such as language-dependent tests, and instructional approaches which lean heavily on language processing and symbolic decoding skills. The cognitive processing burden this creates impacts a student’s ability to truly demonstrate their learning and mastery of the subject; it also perpetuates barriers to meaningful learning for students with exceptionalities. These traditional school structures then may lead to being excluded from more advanced-level STEM courses and future career opportunities. STEM-based education is important for all learners, providing opportunities for developing 21st-century skills integral to the fabric of today’s workforce.

STEM-based education far surpasses concepts in math and science as it is keenly focused on hands-on learning with real-world applications through a cross-curricular lens, all while developing creativity, collaboration, communication, and flexibility, for example. There are many benefits of STEM education beyond scientific literacy; here are just a few:

Written By Janet M. Cozine- The Craig School LS/MS Director

One of the most commonly used reading and writing strategies at The Craig School is R.A.C.E., a design that helps our students support their written responses with evidence from the text.

The acronym is posted almost everywhere at Craig. Readily seeing the mnemonic helps students remember which steps, and in which order to write a constructed response.

We start the R.A.C.E. strategy in reading classes as early as fourth grade, understanding that our emerging readers may only get as far as R (restating the question) and A (answering the question). It’s not always easy for students to answer questions in a formal style. Often their language tends to be more informal, so explicitly teaching the skills of putting thoughts and answers into more formal writing early on will position the students for middle school and the next step to R.A.C.E. the C (citing evidence from the text).

Students are taught to highlight the question words to be used in Restate. When answering the questions teachers are pointing out the connection to Project Read Written Expression as well. The more opportunities the students have to recognize the interrelationships of the strategies the greater the chance for generalization.

In sixth grade, we pull the instruction of Restate and Answer into Science and Social Studies classes. Teacher modeling is still required, but we are now looking for the skill of Restate and Answer the question to become more automatic. When students are ready, Citing the source is introduced in all of the content areas tying in Project Read Report Form, to support where examples and details are found in the text. Scanning for information can be challenging so we start simply, giving the page number to find the evidence and then scaffolding from there. The students are then taught to underline the evidence from the text that supports their answers. This will prepare them for the hardest part of RACE - E - explain. Students need to be taught to explain their evidence without just restating. We present simple sentence stems that help supports their explanation. The stems will eventually be removed once the students understand how to show why the textual evidence matters. We use the detective analogy. A detective collects a lot of the evidence and then has to explain how each piece of evidence proves his case.

The process of using R.A.C.E. is woven throughout the Craig curriculum and throughout the student’s years at Craig. It becomes more sophisticated as time goes on and requires lots and lots of practice. With that practice, we have found that our students learn to do what every good writer does.

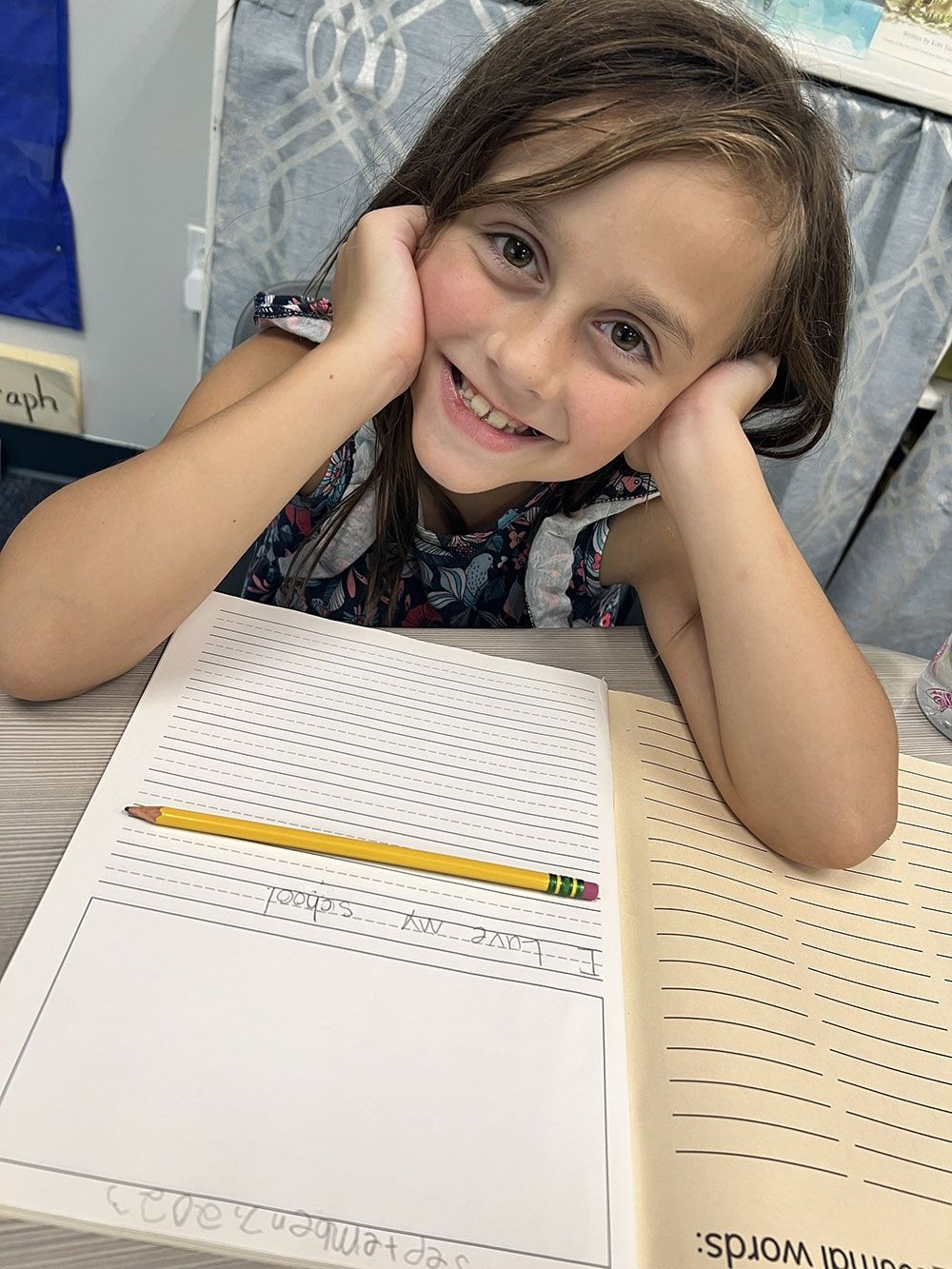

Simply put, books are powerful. They provide opportunities for imagination, discovery, deep thinking and learning, and may even lead to truly transformative experiences. Our students have a complex history with the power of the printed word. For some, the frustration is so palpable that books begin to be viewed as a roadblock they wish not to tackle. For others, there may be what presents as indifference to reading or even a reluctance to read. What is beautiful to witness at The Craig School is when our students unlock the reading code and gain the skills needed to begin a new relationship with books, reaping the benefits of deep understanding and rich comprehension. Walking the hallway of Wilson Hall just this morning, I found students excitedly sharing aloud stories they wrote and reading passages from books they love.

Each March, The Craig School celebrates National Reading Month, through Read Across America events, such as a Dr. Suess writing workshop in our high school, a special Dr. Suess-themed breakfast for lower and middle school students, and a school-wide “Drop Everything and Read!” event. This is followed up with our annual Scholastic Book Fair, March 9th-11th located in Wilson Hall on the Lower and Middle School. Each is intentionally part of our programming to enhance our students’ relationship with books.

Read Across America, which is also the birthday of Dr. Suess, is celebrated each year on this very day, March 2nd. It began as a means for parents, teachers, and communities to help young people uncover the fun and curiosity that reading can bring to us. Today, our hope remains that through these focused activities during National Reading Month, our students find a renewed sense of joy in reading. As students master lower-level reading skills (e.g. phonics, phonemic awareness, etc.) and begin to acquire more complex and nuanced skills (e.g. fluency and comprehension), focused reading-related festivities, such as Read Across America, are tools The Craig School uses to promote a positive attitude toward reading and to begin a new page in our students’ journey with books. Additionally, I find these two research-backed suggestions helpful in our thinking about how to spark our students’ joy of reading:

Developing skilled reading is a lifelong process. At The Craig School, we provide students with the tools and strategies needed to fully comprehend what they read, in addition to experiences that promote positive moments in which to discover the power found within books.

At The Craig School, we speak often about our goal to foster independent learners. Part of this process requires a closer examination of our students’ needs and the compensatory strategies, interventions, or instructional strategies central to creating an environment conducive to their most optimal growth. This week, I turn our attention to working memory and its role in learning. In short, working memory is the small amount of information that is held in the mind while simultaneously understood and used. It has auditory or verbal components best described as a sort of recording of what you hear containing words, numbers, and sentences, and visual-spatial elements described as a visual representation of information in the “mind’s eye” (images, pictures, and information about location in space).

Working memory impacts reading, information processing, problem-solving, remembering instructions, and attention. Each is important in our students’ journey as scholars. For example, word problems in math can be challenging because students must attend to clue words for operations, clue words for numbers, as well as clue words for sequencing or ordering of events all at the same time. Specific to reading, working memory provides a link to information held in long-term semantic memory stores with the meaning and pronunciation of words. Working memory impacts spelling, written expression, reading comprehension, and even fluency or automaticity. When I think about our students who struggle with working memory, I imagine them trying to hold onto incoming information while also using that same information for a task, each action taxing their cognitive load and leaving less space for the actual learning process to occur. This may be cognitively and sometimes physically exhausting for students.

Even more important than understanding working memory, is translating this understanding into actionable practice in the classroom to more effectively support our students’ learning. Faculty at The Craig School incorporate the following to support students with their working memory demands:

teaching students how to use and when to use reference sheets, memory aids, and graphic organizers,

keeping directions concise and clear as well as repeating directions,

breaking tasks into smaller chunks,

providing information through multiple means: speak it, show it, and model it method,

applying visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and tactile instructional modalities to engage learning,

increasing the meaningfulness of the material by providing examples students can relate to, and

developing routines in classroom procedures, like routines for turning in completed work, which then after repeated practice, begins to internalize and automatize, thus reducing the cognitive load demand.

While this list is not exhaustive, it does provide a glimpse into how thoughtfully and intentionally, we approach our work with your students. Please know, there are many things parents and teachers can do to understand and support our students’ working memory. As you get to know what we call “The Craig School Toolbox” you will notice commonalities in classroom settings such as highly structured and well-organized classroom environments, direct, explicit instruction, along with specific instructional practices, for example, cueing, the use of checklists, reference sheets, and reminder systems, among many other strategies. There are even things that parents can do at home, that are appropriate for our young and our old students alike, such as only giving one task command at a time, rather than a string of instructions and using verbal and visual cues to build consistent home routines, think post-it note reminders or asking your child to verbally repeat the task aloud (Child Mind Institute). While this is just a snapshot of our educational approach through the lens of one specific challenge many of our students face, I encourage continued conversation on how we can partner to best meet the needs of our students. I appreciate time spent with you in partnership and support of fostering our students’ best selves.

For more information on ways of giving or to make a donation online you can clicking here.