Individualized education programs that focus on learner competencies enhance student growth and increase parental involvement.

Teachers Connecting to Advance Retention and Empowerment.

In the Spring of 2020, T-CARE offered its first special edition, one with the theme of Teaching, Leaming, and Working in a Remote Environment. In my editorial, I shared that “Many wrote in and, based on the responses, we created a new section for this issue only: Reflections in the Time of COVID-19." How devastating to realize that, almost two years later, we are not reflecting on a time gone by, but reflecting on a trauma we are still experiencing. This is our third special issue in fact, following one on Equity, Access, and Social Justice in Fall 2020. Dealing with our own traumas and special circumstances, the CTL did not publish a T-CARE issue earlier in 2021. This, the only issue in 2021, has the theme of If I Had Known Then...

Introduction & Rationale

Background

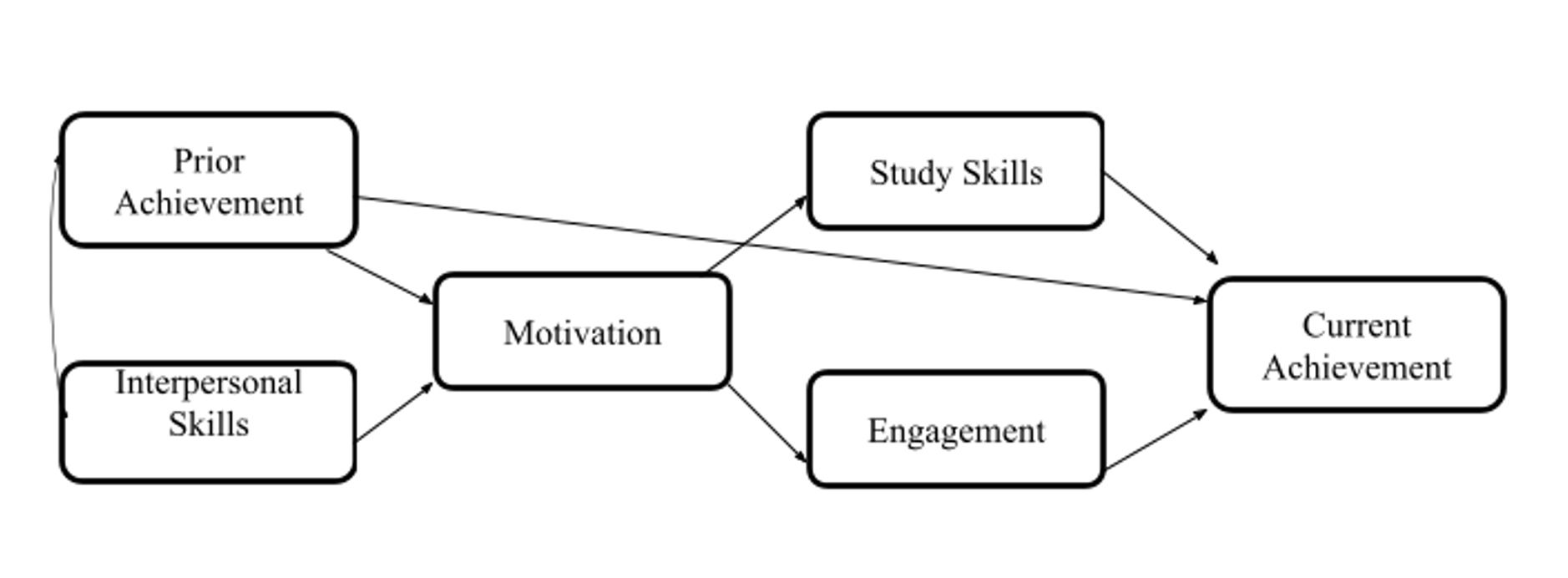

Teens with ADHD experience greater levels of academic impairment than students without ADHD. Academic enablers, non-cognitive skills and behaviors, like study skills, engagement, motivation, and interpersonal skills are essential components to optimal academic attainment. For students with ADHD, these skills tend to be underdeveloped. This study explored the attitudes, thoughts, and perspectives of students in high school diagnosed with ADHD in regards to their challenges, their strengths, and their experiences as students. As children gain more autonomy, listening to their voice is an important step on their path to self-advocacy. To inform the understanding and development of models for effective intervention that are accepted and readily adopted by teenagers with ADHD, interviews conducted with 16 students examined academic enablers from their perspective. Results from these interviews create an authentic context for exploring student perspectives about (a) the social self, the student learner in relation to teachers and peers, and (b) the individual self, and (c) the student’s use of self-regulation, self-management, and self-expression as they become more autonomous individuals with increased responsibilities for their own learning. This study examines high school students’ experiences and perspectives of their ability to learn and experiences in the classroom, the interventions teachers have taken with them, exposure to stigmatization, engagement in student agency, diagnostic labeling effects, and their self-concept (Owens & Jackson, 2017; Wiener & Daniels, 2016).

Need for Study

Persisting into adolescence and adulthood, educational impairment impacts 50 to 80% of youth with ADHD (DuPaul, Stoner, & Reid, 2014). Critical skills for students in secondary schools include the ability to engage executive functions and self-regulatory behaviors, such as planning and organization, all predictive of future academic attainment (Barkley, 1997; Volpe et al., 2006).

A large body of research exists exploring the role of behavior in academic attainment for elementary students as well as students in college. However, the cannon of literature exploring the experiences of teenagers with ADHD in relation to their acquisition of academic enablers leading to educational attainment as they navigate more autonomy, less parent, teacher, and school supports and structures, and increased independence are scant (Bolic Baric, Hellberg, Kjellberg & Hemmingsson, 2016; DiPerna, 2006; Kent et al., 2011; Wiener & Daniels, 2016; Wu & Gau, 2013).

Research shows that teenagers may be resistant to academic supports they view as stigmatizing or labeling (Bussing et al., 2016; Owens & Jackson, 2017). To inform understanding and development of models for effective intervention that are accepted and readily adopted by teenagers with ADHD, a closer look at academic enablers from their position is essential (Wei, Yu & Shaver, 2014).

Research Questions

Methods

Interview Questions

Emergent Themes

Individualized/Modulated Pacing

“So like, I also like individualized learning. So like, here, it's amazing because like, there's smaller class size and then there's also study hall that you can go to. And I really like that because then you get more time with the teacher individually. So I like it, I like when I know that I can have help individually.”

-JA, 12th grade

Teacher Directed Learning and Attention

“I'm a very, I learned by talking through things and or doing them. If a teacher is willing to talk with me about the subject, not not particularly be very restrictive on it. My brain has a very odd way of making connections. So a lot of the times if a teacher is willing to go with me on one of my weird metaphors I'll understand the subject...it just...it helps me to talk it out and say, Okay, well, it's like this and this, right? And if they say yes, then that's great. If it's no, then it's another try. And I've always found that the best way for me to learn.”

-OL, 12th grade

“And so we wrote it all down, and then we put how much time I think it's going to take, so that helped with my organization, because then that actually, it actually worked because I spent a certain amount of time on each thing and I got it done. So, she's, she's amazing with that. She's really great at organization.”

-SB, 11th grade

Passive Peer Mentoring

“Yeah, because I know that other people are you know, more focused and can do things faster. So if I have …it's sort of like cross country running, if I have someone who can pace myself. Then I can, I work a lot better.”

-FP, 10th grade

“...not doing it in my room. I just can’t concentrate. I need someone kind of there, to, like help me. Like, it’s weird. If someone’s like sitting next to me while I’m doing work, I’m doing it much better than when I am by myself.”

-KS, 10th grade

Self-Concept: Identity

“When I was a lot younger, my mom went to multiple doctors and asked them if I was autistic. And, you know, so on and so forth. There were quite a few different diagnoses that came up over the years. So, needless to say, the ADHD wasn't really a new thing for me to be diagnosed as…And parenting is hard. And when you can't find an answer for why your child is behaving like this, or why your child isn't behaving like this. It can be scary, which I understand. And I also have to know that that wasn't the correct behavior that, you know, they should have been a little more considerate.”

-OL, 12th grade

Self-Concept: Belonging

“I felt like I was different from everyone else…That was when I was first diagnosed. But then, like, as I learned more about ADHD, I’m like, no, I’m no different. I just have this thing….that kind of makes it harder for me to learn and focus.”

-JA, 12th grade

Self-Management

“Because in order to keep myself physically organized, I have to keep myself mentally organized. So like to have like to have it all organized. I try to stay on top of it, if not ahead of what's going on. Not only because I really don't like doing homework outside of the school hours, but also because when I do homework outside of school hours, it's kind of like, I get more distracted and more like, oh, I don't want to do this.”

-SS, 11th grade

Self-Awareness

“I been very good about adapting and knowing exactly what I need when I need it. Because otherwise, I’m just not going to succeed.”

-OL, 12th grade

Attention/Focus

“I'll be talking and all of a sudden, my mind just goes faster than I'm talking. I'm just like…I start fumbling on words. I'm like, I have to chill for a second. I can't talk right now. Because my mind is already like, 10 words of head of what I was already saying…”

-KS, 12h grade

Self-Expression

“I like to do whatever I can get my hands on, basically. I will do anything I can. Like, I can do fashion design. I can sing songs. And I’m learning to write songs. I’m just great at painting. I’m great at a lot of things.”

-KQ, 9th grade

Conclusions

Results from the study revealed the challenges that teenagers with ADHD face along with their perspectives on identity, self-expression, and sense of belongingness. Balancing teacher-led scaffolding and collaborative learning opportunities with peers may be one means to address the interplay of dependence moving to independence as a learner. As students mature, their responsibilities are expected to increase. However, these 16 participant interviews and observations indicate there are varying levels of student readiness to move in the direction of self-agency and autonomy. Many teens continue to need support with basic study skills like organization, prioritization, planning, and time management. Additionally, engaging the student in work that is meaningful to them gives them a greater sense of ownership over the process of learning, and increases their ability to attend to the task. Teachers who give students choice in the type of task (e.g. essay instead of multiple choice test, or project rather than worksheet) are able to leverage the students’ buy-in and innate motivation to get the work done. Teachers are encouraged to allow the students to use multiple means to represent their learning, encouraging the student to tap into their affinity for self-expression. Finally, increasing relevant pre-service training for teachers would not only benefit students with ADHD, but all learners so that teachers are equipped with a toolbox of instructional strategies and interventions that far exceed the traditional needs in the high school classroom.

Postsecondary Planning in the Age of COVID

In the middle school years, parents and oftentimes students alike, begin to turn their attention to life beyond the hallowed halls of The Craig School by exploring college and career possibilities for their student. Parents new to our school may not be aware of our end-to-end College Counseling and Career Placement services. While the lion’s share of activities generated out of our college and career office relate to high school, Lindsey Skerker, Director of College Counseling and Placement, is here for all Craig School parents, whether your child is in 7th grade or in 11th grade.

Through supportive and differentiated guidance specific to each student, their educational journey, and their dreams of the future, Lindsey works with students and families to navigate the complexities of understanding one’s learning proclivities and uncovering “best fit,” all the while empowering students for success in the college and career application process. This personalized approach accommodates students’ needs and strengths, tunes in to building self-advocacy and self-awareness skills, and encourages our students to find schools catered to their unique interests.

I encourage parents, especially our middle and high school parents, to join Lindsey for a webinar on October 27th at 7 pm, Postsecondary Planning in the Age of COVID. Lindsey will walk us through some of the sweeping changes to the college admissions & post-high school landscape that have occurred since 2020.

The path to college and post-secondary career is both a celebration and an extension of the students’ learning experience as a Craig School Badger. For a sneak peek into the scope of the webinar, please enjoy this blog post from The Craig School’s Director of College Counseling and Placement, Lindsey Skerker. I look forward to “seeing” you next Wednesday night!

Best,

Dr. Kara A. Loftin

Head of School

Postsecondary Planning in the Age of COVID

By Lindsey Skerker, Director of College Counseling and Placement at The Craig School

Within the past 18 months since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, K-12 and higher education has been forced to rapidly adapt. It has been hard enough for educators, let alone students and families, to keep up with these countless changes and challenges. COVID has been incredibly difficult for the education sector, with lasting ripple effects which will impact this generation of learners for years to come. However, I believe it has also brought about certain equitable adaptations that would have never occurred so quickly in the “before COVID era.” Especially as a counselor for students with learning disabilities (LDs), I have been able to witness some silver linings in the postsecondary planning process, many of which will have an immense impact on the graduating Classes of the 2020s and beyond.

Before COVID entered our vernacular in 2020, many of our LD students were not just struggling with their usual ADHD, dyslexia, dyscalculia, dysgraphia, executive functioning challenges, etc. but much of that was compounded by mental health issues such as anxiety and depression. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), 20% of American adults and 17% of American youth (ages 6-17) experience a mental health issue in their lifetime. These mental health stats along with the “The Varsity Blues College Admissions Scandal” (one of the biggest news stories of 2019), and the combination of a once-in-a-century pandemic was a huge wake-up call to the higher education sector. The need for a more holistic and less mental-health-shattering college admissions process was more apparent than ever before.

When counseling students from the Class of 2020 and onwards, I have called them the pioneers in this “Wild West” new world of COVID and beyond. As colleges & universities became “test-optional” or “test-blind” in the blink of an eye in 2020, that in and of itself was a huge marker for equitable change and forward thinking in the college admissions process.

These “test-optional” or “test-blind” schools (which do not require SAT or ACT scores in the admissions process), seem like they will be here to stay for a large portion of colleges and universities. Some colleges have pledged to keep these policies through at least the Class of 2023, and others like the University of California system have done away with them altogether (note: please refer to FairTest.org for further “test-optional” colleges). Even before 2020, it is also important to realize that certain colleges have been part of the “test-optional” movement for decades! Now though, more schools are finally catching up and putting greater emphasis on other pieces of the college application, like the personal statement essay, GPA, and letters of recommendation. This increase towards a more holistic approach to the application review process has kept students’ mental health at the forefront. Finally, college admissions as an entity understands the stressors and anxieties that applicants face, for much of our society has had to grapple with staying healthy both physically and mentally. This greater overall understanding of student well-being and the major admissions adaptations have been a huge silver lining in the postsecondary process.

I like to think that another silver lining is the increased amount of autonomy and options that now exist in education and the postsecondary process. Students have experienced in-person, hybrid, and remote models of learning over the past year and a half. They have come to recognize what works best for them as a student. These experiences can hopefully act as a reflective tool to determine a potential college or career path, as students and families have come to an acute understanding of what the best learning environment is – whether that’s online, in-person, or hybrid. This individualized approach coupled with more autonomous educational opportunities will hopefully benefit students now and in the future.

Finally, I’ve appreciated the greater emphasis on really examining the “why” behind a postsecondary decision, especially during this era. Instead of just going to college because that is what a student thinks they are “supposed” to do, there has been much more of a step back to ask the “why” behind it. Students and families have been forced to consider if they’ve wanted to attend (and pay for) college classes online last year or in-person now with COVID lurking around campus corridors. Since Spring of 2020, many high school seniors across the US fully re-evaluated their decisions, and some chose to take a gap year or stay close to home to gain work or volunteer experience. I think that this era has really made our society question past “norms” that perhaps have been damaging to some students with LDs and mental health issues. People have hopefully recognized by now that just because students are chronologically 18 years old doesn’t mean that all of them are ready at the exact same time to do the exact same thing! A special shoutout to Leslie Josel for sharing the “executive age” concept in her recent Craig School webinar, where she explained that students with ADHD and executive functioning deficits can lag a few years behind peers in terms of organization and independence.

This is certainly an important piece with our LD population, and then couple this “executive age” concept with delays tacked on thanks to COVID, and we are again left to examine the big questions behind postsecondary decisions. Overall though, I think we can finally begin to acknowledge that some students need extra time to mature, or perhaps they have different priorities now, and I consider that a huge leap forward in changing the cultural narrative around these types of post-high school graduation conversations. For those who are interested in exploring these topics further, I’d like to invite you to attend the upcoming webinar on Wednesday, October 27th at 7 pm where I will be discussing Postsecondary Planning in the Age of COVID.

Thank you, and I hope to “see” you there!

Lindsey Skerker,

Director of College Counseling and Placement at The Craig School

Executive functions are inextricably linked to learning and problem-solving. A common misconception I hear regarding students who may struggle with executive functioning skills is that this struggle is synonymous with challenges linked to ADHD. While executive function challenges may accompany ADHD symptomology, it is also true that a student who exhibits weaker or underdeveloped executive functioning skills, may not fit diagnostic criteria for ADHD. To be clear, executive functions play a crucial role for learners of all abilities throughout their school years, whether or not these skills are typical, delayed, or labeled dysfunctional for any particular student. They are developmentally-related functions that help navigate both educational and life-related activities; they help us organize our behaviors and tune out distractions so that we may accomplish our goals.

As an educator, I believe I have a responsibility to understand the links between neuroscience, cognitive psychology, and education so that we, at The Craig School, implement classroom settings, strategies, and educational programs that build upon these critical self-management skills, the executive functions.

Understanding written text is one of the most important abilities students must acquire during their school years. Reading comprehension difficulties may exist despite adequate decoding skills. Decoding skills involve knowledge and subsequent application of letter-sound relationships and letter patterns, language comprehension (vocabulary, morphology, oral comprehension for example), and word identification.

Skilled reading focuses on reading comprehension, the “process of simultaneously extracting and constructing meaning through interaction and involvement with written language.” (RAND Reading Study Group, 2002). The discrepancy between adequate decoding and the ability to understand written text indicates other contributing cognitive processes for successful reading comprehension beyond these foundational reading or decoding skills. There are four core executive functions related to reading comprehension: cognitive flexibility, planning, inhibition, and working memory. As students progress from grade to grade, questions aligned to inference making and evaluation, rather than literal extraction, become more and more important for accurate understanding and subsequent transfer of knowledge. The following is a taste of how each of these four core executive functions impacts students’ ability to comprehend:

While applicable for all types of learners, I can not emphasize enough the role of executive functions when examining classroom instruction and approaches for students with learning differences as many times challenges in executive functioning mask students’ academic ability and capabilities. At The Craig School, you will hear often of our goal to move students toward increased independence as learners. This is a process; it takes time and it also requires us to provide both compensatory strategies and focused intervention of these underlying cognitive processes central to academic success. As you get to know The Craig School Toolbox and our approach to fostering executive functioning development in all of our students, you will notice commonalities in classroom settings such as highly structured and well-organized classroom environments, along with specific instructional practices like cueing, the use of checklists and reference sheets, reminder systems, grouping information into chunks, and the use of mnemonic devices for learning, among many other strategies.

A social state or condition; a fellowship; a group sharing common characteristics; a unified body of individuals. Community, a hallmark of great schools, is at its core a culture of belonging, demonstrated daily through positive, supportive interpersonal, bidirectional relationships among teachers, staff, administration, parents, and students alike. Students who find themselves in communities of belonging, find classrooms where expressions of personal thoughts, feelings, and experiences are welcomed, acknowledged, and understood. Seemingly diverse individuals are able to unite under that which is common. Creating a school community of belonging rooted in trusting relationships is intentional; it is challenging. It is a pursuit with no set point ending; there are constant undulations. What we know, however, through decades of research is that a school community characterized by supportive relationships provides an environment rich for academic growth, school engagement, altruistic and ethical actions, and the development of social and emotional competencies. It is through these positive and supportive relationships that belongingness blossoms.

Many students and families find themselves at The Craig School after years of frustration from previous school experiences. Trust, so integral to positive, supportive school relationships, has dissolved. This could be trusted in the “system” of education in general or with the individual components. Trust, however, is acutely important on our journey as parents and educators to unlock our students' capabilities, bolster their self-awareness and self-esteem, and help them tap into all of their potential greatness. And, I believe, collectively, this is what we want for each of our students.

Hoy and Tschannen-Moran (2003) define trust as “an individual’s or group’s willingness to be vulnerable to another party based on the confidence that the latter party is benevolent, reliable, competent, honest, and open.” For some of you, you have been part of our community for many years now, and for others, we are just beginning our relationship and trust-building. I believe in the mission of this wonderful school and I believe in the goodness among our faculty and staff who truly put your children first.

My goal for us as a community of parents, guardians, teachers, staff, students, and administrators, is to aspire for relationships marked by these core values of (a) benevolence, which may be defined as the confidence that we have the best interests of your student at heart, (b) reliability, or the extent to which you are able to depend upon The Craig School to come through for your student, to act consistently, and to follow through, (c) competence, that is, the belief that we are able to perform the tasks required of us as educators entrusted to the care of your child, (d) honesty, the ability of each faculty, staff, and administrator to demonstrate character marked by integrity and authenticity, (e) openness, a bi-directional flow of information so that we may partner in the work we do as a school community all for the benefit of your child (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 1998; Brewster & Railsback, 2003).

The road to The Craig School is different for each student. Whichever path led you here, I am grateful. It is a privilege to work with your children, to partner with you, and to build an intentional community of belonging marked by trusting supportive relationships.

What if rather than viewing learning disabilities as deficits, we viewed them as part of the natural variations of the human genome? Sometimes called the social model of disability or neurodiversity, this view holds that dyslexia or specific learning disability, for example, is merely but one component of identity and functioning, not its totality, and is best defined as the “gap between a person’s capacities and the demands of the environment” (Wehmeyer, 2020). An example of this framework is a student who struggles with reading and is presented only with print curricular resources. By providing one means to access the curriculum, the student is hampered in how much he or she is able to learn. However, this same student, presented with speech-to-text technology or audiobooks, now has access to learn more substantially. The person is still the same, the environment shifted. At The Craig School, we believe that a strengths-based approach primes students for learning and that with the right environment, all students can and will succeed.

REPOSTED FROM nj.com - READ FULL ARTICLE HERE

Reading does not come naturally, easily or incidentally for countless children. It is a tough hill to climb that takes patience, time and tenacity. Through decades of research, we understand that dyslexia can vary widely in students from a phonological deficit, orthographic deficit, a naming-speed deficit or a combination of one or more of these challenges. Additionally, adding on processing speed, working memory, rapid automatic naming and visual-verbal paired-associate learning challenges, the complexity increases exponentially and the need to use a proven, evidence-based approach is more critical than ever.

REPOSTED FROM NJ.COM - READ FULL ARTICLE HERE

Throughout the year, I have written about strengths-based education for students with exceptionalities, the importance of developing a strong sense of self-efficacy and creating safe, nurturing, positive spaces for learning. Each is related to the broader educational implications of our mindset around disability. Something I think about often is how schools would function if rather than viewing learning disabilities, as deficits, we viewed them as part of the natural variations of the human genome? Sometimes called the social model of disability, the person-environment-fit, or even the neurodiversity model, this view holds that dyslexia or specific learning disability, for example, is merely but one component of identity and functioning, not its totality, and is best defined as the “gap between a person’s capacities and the demands of the environment” (Wehmeyer, 2020). An example of this framework is a student who struggles with reading and is presented only with print curricular resources. By providing one means to access the curriculum the student is hampered in how much they are able to learn. However, this same student, presented with speech-to-text technology or audiobooks now has access to learn more substantially. The person is still the same, the environment shifted.

By moving our thinking from disability as a deficit or something needing to be fixed or cured to a model built more on capacity-building and environmental changes to support learning, a student’s educational experiences are enhanced and their strengths are leveraged for deeper learning and meaning-making. Students benefit from teachers who provide multiple means of representation, multiple means of expression and action, and multiple means of engagement to meet their students’ individual needs. A simple example is the use of a graphic organizer with reduced text to bridge the gap between challenges with reading comprehension and the student’s ability to recall information in an ordered sequence. Fundamental competencies, such as literacy skills like inference making at the paragraph level, are not ignored but addressed. Couple that foundational work with multiple access points to curriculum that matches the increased demands of literacy throughout the school years and the needs of the individual and we have lessened the gap between ability and environment. Daily, The Craig School balances the educational needs of our students by providing ample instructional time for addressing their greatest needs while also supporting the development of strengths, all the while recognizing that our students are fully human, ever-evolving, and full of ability.

Within this new mindset, the language we use and the labels we attach to differences are also important factors to consider. A glance at the above two paragraphs highlights the use of the word “disability” as a common descriptor. We function in a world where to get the supports and services that our students need, they are “classified” and this happens after identification of a disorder or disability. This practice of labeling inherently impacts how one thinks of themself and how one is perceived by others. In turn, educational decisions regarding when students are “ready” to learn and in what ways they are capable of learning follow.

What I am so proud of at The Craig School is that we cultivate and support our students’ positive identities as learners. We partner with you to build their capacity through targeted, personalized learning experiences that remove barriers to learning. Finally, we design the broader curriculum to allow for greater access and participation from each of our students. Our students recognize they are capable of so much more than the limiting beliefs they may have once experienced.

I leave you with this powerful statement of truth-telling from Rapport-Schlichtmann, Boucher, and Evans (2018) that applies to all disability types:

The challenges of dyslexia are real, but they are limiting only to the extent that we allow them to be. The moment we start defining a person by deficits, we undermine their capacity to be successful, and there is no space to develop strengths and positively adapt. If we instead build the capacity of students with dyslexia to improve on their areas of weakness, as well as build on their individual and unique areas of strength, we begin to create the foundation for thriving in learning and life.

“When a flower doesn’t bloom, you fix the environment in which it grows, not the flower.” (Alexander den Heijer). This one phrase perfectly sums up the educational philosophy of The Craig School. As educators, we believe that children are beautiful, whole and perfect beings, and they are messy, they are works in progress, they represent the wonder of possibility. We believe that it is not the child who needs to be somehow “fixed;” rather, that when our children are given the right opportunities, support, kindness and genuine care, they begin to blossom and to move more fully into their unique potential.

REPOSTED FROM NJ.COM - READ FULL ARTICLE HERE

For more information on ways of giving or to make a donation online you can clicking here.