Introduction & Rationale

Background

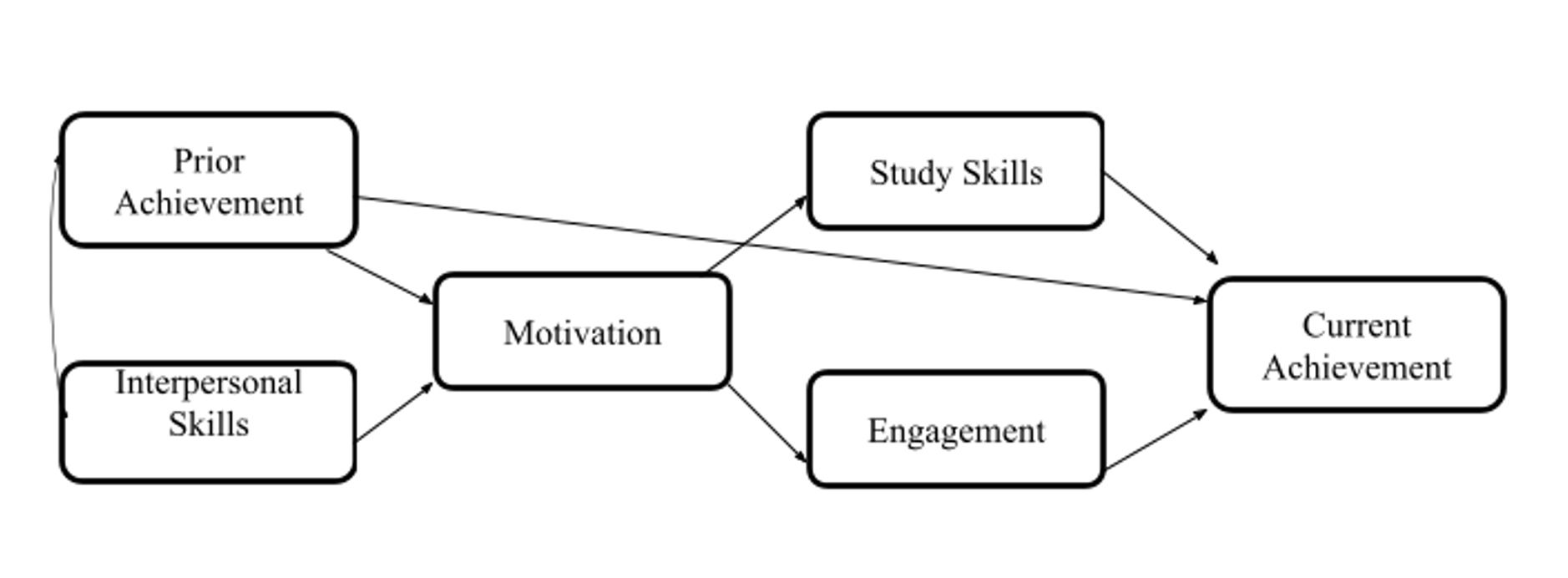

Teens with ADHD experience greater levels of academic impairment than students without ADHD. Academic enablers, non-cognitive skills and behaviors, like study skills, engagement, motivation, and interpersonal skills are essential components to optimal academic attainment. For students with ADHD, these skills tend to be underdeveloped. This study explored the attitudes, thoughts, and perspectives of students in high school diagnosed with ADHD in regards to their challenges, their strengths, and their experiences as students. As children gain more autonomy, listening to their voice is an important step on their path to self-advocacy. To inform the understanding and development of models for effective intervention that are accepted and readily adopted by teenagers with ADHD, interviews conducted with 16 students examined academic enablers from their perspective. Results from these interviews create an authentic context for exploring student perspectives about (a) the social self, the student learner in relation to teachers and peers, and (b) the individual self, and (c) the student’s use of self-regulation, self-management, and self-expression as they become more autonomous individuals with increased responsibilities for their own learning. This study examines high school students’ experiences and perspectives of their ability to learn and experiences in the classroom, the interventions teachers have taken with them, exposure to stigmatization, engagement in student agency, diagnostic labeling effects, and their self-concept (Owens & Jackson, 2017; Wiener & Daniels, 2016).

Need for Study

Persisting into adolescence and adulthood, educational impairment impacts 50 to 80% of youth with ADHD (DuPaul, Stoner, & Reid, 2014). Critical skills for students in secondary schools include the ability to engage executive functions and self-regulatory behaviors, such as planning and organization, all predictive of future academic attainment (Barkley, 1997; Volpe et al., 2006).

A large body of research exists exploring the role of behavior in academic attainment for elementary students as well as students in college. However, the cannon of literature exploring the experiences of teenagers with ADHD in relation to their acquisition of academic enablers leading to educational attainment as they navigate more autonomy, less parent, teacher, and school supports and structures, and increased independence are scant (Bolic Baric, Hellberg, Kjellberg & Hemmingsson, 2016; DiPerna, 2006; Kent et al., 2011; Wiener & Daniels, 2016; Wu & Gau, 2013).

Research shows that teenagers may be resistant to academic supports they view as stigmatizing or labeling (Bussing et al., 2016; Owens & Jackson, 2017). To inform understanding and development of models for effective intervention that are accepted and readily adopted by teenagers with ADHD, a closer look at academic enablers from their position is essential (Wei, Yu & Shaver, 2014).

Research Questions

Methods

Interview Questions

Emergent Themes

Individualized/Modulated Pacing

“So like, I also like individualized learning. So like, here, it's amazing because like, there's smaller class size and then there's also study hall that you can go to. And I really like that because then you get more time with the teacher individually. So I like it, I like when I know that I can have help individually.”

-JA, 12th grade

Teacher Directed Learning and Attention

“I'm a very, I learned by talking through things and or doing them. If a teacher is willing to talk with me about the subject, not not particularly be very restrictive on it. My brain has a very odd way of making connections. So a lot of the times if a teacher is willing to go with me on one of my weird metaphors I'll understand the subject...it just...it helps me to talk it out and say, Okay, well, it's like this and this, right? And if they say yes, then that's great. If it's no, then it's another try. And I've always found that the best way for me to learn.”

-OL, 12th grade

“And so we wrote it all down, and then we put how much time I think it's going to take, so that helped with my organization, because then that actually, it actually worked because I spent a certain amount of time on each thing and I got it done. So, she's, she's amazing with that. She's really great at organization.”

-SB, 11th grade

Passive Peer Mentoring

“Yeah, because I know that other people are you know, more focused and can do things faster. So if I have …it's sort of like cross country running, if I have someone who can pace myself. Then I can, I work a lot better.”

-FP, 10th grade

“...not doing it in my room. I just can’t concentrate. I need someone kind of there, to, like help me. Like, it’s weird. If someone’s like sitting next to me while I’m doing work, I’m doing it much better than when I am by myself.”

-KS, 10th grade

Self-Concept: Identity

“When I was a lot younger, my mom went to multiple doctors and asked them if I was autistic. And, you know, so on and so forth. There were quite a few different diagnoses that came up over the years. So, needless to say, the ADHD wasn't really a new thing for me to be diagnosed as…And parenting is hard. And when you can't find an answer for why your child is behaving like this, or why your child isn't behaving like this. It can be scary, which I understand. And I also have to know that that wasn't the correct behavior that, you know, they should have been a little more considerate.”

-OL, 12th grade

Self-Concept: Belonging

“I felt like I was different from everyone else…That was when I was first diagnosed. But then, like, as I learned more about ADHD, I’m like, no, I’m no different. I just have this thing….that kind of makes it harder for me to learn and focus.”

-JA, 12th grade

Self-Management

“Because in order to keep myself physically organized, I have to keep myself mentally organized. So like to have like to have it all organized. I try to stay on top of it, if not ahead of what's going on. Not only because I really don't like doing homework outside of the school hours, but also because when I do homework outside of school hours, it's kind of like, I get more distracted and more like, oh, I don't want to do this.”

-SS, 11th grade

Self-Awareness

“I been very good about adapting and knowing exactly what I need when I need it. Because otherwise, I’m just not going to succeed.”

-OL, 12th grade

Attention/Focus

“I'll be talking and all of a sudden, my mind just goes faster than I'm talking. I'm just like…I start fumbling on words. I'm like, I have to chill for a second. I can't talk right now. Because my mind is already like, 10 words of head of what I was already saying…”

-KS, 12h grade

Self-Expression

“I like to do whatever I can get my hands on, basically. I will do anything I can. Like, I can do fashion design. I can sing songs. And I’m learning to write songs. I’m just great at painting. I’m great at a lot of things.”

-KQ, 9th grade

Conclusions

Results from the study revealed the challenges that teenagers with ADHD face along with their perspectives on identity, self-expression, and sense of belongingness. Balancing teacher-led scaffolding and collaborative learning opportunities with peers may be one means to address the interplay of dependence moving to independence as a learner. As students mature, their responsibilities are expected to increase. However, these 16 participant interviews and observations indicate there are varying levels of student readiness to move in the direction of self-agency and autonomy. Many teens continue to need support with basic study skills like organization, prioritization, planning, and time management. Additionally, engaging the student in work that is meaningful to them gives them a greater sense of ownership over the process of learning, and increases their ability to attend to the task. Teachers who give students choice in the type of task (e.g. essay instead of multiple choice test, or project rather than worksheet) are able to leverage the students’ buy-in and innate motivation to get the work done. Teachers are encouraged to allow the students to use multiple means to represent their learning, encouraging the student to tap into their affinity for self-expression. Finally, increasing relevant pre-service training for teachers would not only benefit students with ADHD, but all learners so that teachers are equipped with a toolbox of instructional strategies and interventions that far exceed the traditional needs in the high school classroom.

Sitting down to write this blog today, I find myself wanting to express thoughts about my passion for educating students with learning disabilities, the joy of teaching, and being part of those “aha” moments when a student finally breaks through and is able to not only understand a concept but to synthesize understanding and even transfer their knowledge to other meaningful moments of discovery. I yearn for our discourse to reflect the values, purpose, and mission of The Craig School and our conversation filled to the brim with the excitement of a new school year and the rich possibility that accompanies new beginnings.

Nonetheless, at the forefront of my thoughts this week is an article I recently read comparing the national current educational climate as a see-saw of balance between Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and Bloom’s Taxonomy, an educational theory on the hierarchy of learning that begins by first remembering, then understanding, followed by applying, analyzing, and evaluating information, finally culminating in the production of new or original work, called the creative stage of learning.

Teachers are busy polishing lesson plans, writing learning targets, and creating engaging and meaningful learning opportunities while also fully cognizant that a student’s basic needs must first be met to allow for learning to happen, to prime the pump, if you will, for the most optimal learning experiences moving a student to the realization of their full potential. On a very basic physiological level, our students need food, water, and shelter. In this basic level Maslow includes safety. According to Maslow, safety is the experience of order, predictability, and a sense of control of one’s own life. It is at this crossroads where I, along with countless educators find myself as we prepare for a new year full of learning and growth. We are balancing the real-life issues of the present unknown with our plans for bringing out the best in all of our students.

Planning for our school opening on September 3rd, we are remembering “Maslow before Bloom.” At The Craig School, this is evident through the preparation of our classrooms and play spaces for healthy and safe learning environments that address not only the present need for sanitization, disinfection, and appropriate health measures for the mitigation of COVID 19, but it is also through the intentional work and focus of our team of Social Clinicians who, partnering with our faculty, foster key tenets of social and emotional health leading to safe spaces for students and safe spaces for learning. These social-emotional aptitudes and skills, such as self-awareness and self-confidence, emotional regulation and stress management, respect for others and empathy, social engagement and relationship building, and finally, ethical responsibility and reflection, create what researcher Amy Edmondson calls “psychological safety” and are necessary to cultivate so that our students’ strengths, capabilities, and intellect can shine. Providing for Maslow before Bloom provides a path to fulfill The Craig School’s mission to address the academic, social, emotional, and moral growth of students with language-based learning disabilities.

This week, I have had a few conversations with parents regarding play in a socially-distanced world. Whether your child is learning remotely or attending school in-person, in second grade, or 12th grade, we acknowledge that times for unstructured movement and peer interactions, commonly called recess or break in a traditional school setting, are essential parts of the school day. This notion is also detailed in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child which states, young people have the "right to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child." Not only is there a body of evidence indicating cognitive performance and attention increases with play, learning components such as memory and retrieval, attention, dexterity, reading, verbal fluency, semantic fluency, and enhanced student motivation and morale are potential outcomes from incorporating play in a school day. Furthermore, studies show the power of play as a tool in the development of important prosocial behaviors; behaviors such as sharing, helping, cooperating, and comforting others. In younger students, recess develops socialization skills that lead to friendships, and for our older students, these socialization skills continue and become more peer-based as adolescents forge a sense of belonging and identity. Throughout the school years, these unstructured times for socialization are one strategy to help students cope with emotions during stressful times; in our current climate, play remains essential to healthy child and adolescent development.

This week we join our fellow New Jersey schools for the Week of Respect, a week dedicated to bringing awareness to the importance of cultivating a healthy, supportive, safe, and positive school climate through character development and social-emotional learning, all with the goal of sustaining a school void of harassment, intimidation, and bullying. At The Craig School, this work is done by creating a physically, emotionally, and socially safe learning environment that values each person as a contributor, is respectful of our community members, promotes collaboration and communication among families, students, and school staff, and most importantly is modeled by our adult community for students. Students with language-based learning disabilities may struggle with receptive language, which is the ability to understand and comprehend spoken language, as well as expressive language, one’s ability to use words to express themselves. These variables alone may impact a student’s risk of victimization. Additionally, students with learning disabilities who also have secondary or comorbid conditions, such as ADHD, may experience increased social skill challenges, creating a need for focused and intentional social-emotional learning opportunities. We recognize that a school’s work to this end is one of progress, rather than a finished, perfect endeavor. At The Craig School, we are committed to continuing this work.

As you get to know my work as an educator, you will find that my approach is rooted in strengths-based learning and assessment wrapped in whole child development. What I have experienced both through academic research and practical boots on the groundwork in the field of learning disabilities is that even though our main objective is to teach our students to read, to write, and to more fully express their intelligence, there are opportunities for tuning into values and characteristics that will serve our students well both now and in the future. As our September 3rd school opening gets closer, conversations with teachers and parents alike have reminded me of the importance of nurturing resilience in ourselves and in our students. If ever we needed to bolster our collective resilience, now is the time.

The resilience movement in education began as a way to better understand why children reach different levels of success when faced with the same challenges and environments as other children. Resilience is a quality our students already possess. Our job is to nurture it. When we help our students recognize and build upon their strengths, abilities, and competencies, their confidence grows stronger and their resilience is fortified. As you have conversations with your children about school reopening, one way that you can draw out or strengthen resilience in your child is to take new and unfamiliar processes and procedures and make them known. This can be done through (a) modeling, learning by imitation, (b) role play, learning what to do and how to do it, (c) constructive feedback or positive reinforcement, and (d) generalization, that is, taking these skills from practice into real-life settings. Resilience is strengthened when children develop positive coping strategies to overcome stressors and challenges. We will be working on resilience in our community so we can all develop positive coping strategies to overcome stressors and challenges together.

The Craig School is uniquely positioned to provide an academically rich environment that is designed for the educational needs of students with language-based learning disabilities. We couple that specific and structured learning with “soft skills” or social-emotional learning (SEL) skills necessary for future success in college, career, and life. The nurturing of social and emotional growth is a core value of The Craig School.

According to the Collaboration for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL), social-emotional learning is “the process through which children and adults understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions.” What we know through evidence-based research as well as our experiences as educators is that social and emotional competencies open a pathway for increased academic success and improved student attitude toward school, thus reducing some of the educational barriers a student may face in a classroom setting. Additionally, schools that emphasize the social and emotional growth of their students whether in the classroom or while at play, increase student agency, voice, and self-awareness, and decrease student stress, anxiety, and social withdrawal.

Community, in its purest form, is a feeling of fellowship with others that springs from shared attitudes, interests, and goals. We, at The Craig School, are such a community. We unite under our common purpose of providing an evidence-based, challenging academic program coupled with nurturing the social-emotional and moral health of our students all in the environment most suited to their needs, with the end goal of a student who is self-aware, self-confident, and able to reach their greatest expectations.

Community is built in the trenches and on the front lines; it is built in our hallways and classrooms. The relationships teachers form with and among their students, with other teachers and staff members, and with their students’ parents and guardians, forge this fellowship. Schools can serve to strengthen a student’s sense of community, their sense of belongingness, through actively cultivating respectful and inclusive relationships—and these relationships begin in the classroom. Dr. Caparulo, Director of our high school, has a signature quote on this email that reads, “No significant learning happens outside of a significant relationship” (James Comer, Professor at the Yale Child Student Center). How true this statement rings. The keys to creating a positive climate and a community of belonging are relationships, and it is through these relationships students blossom and are primed for optimal learning.

Rita Pierson, the late teacher most known for the TedTalk, Every Kid Deserves a Champion once said, “How powerful would our world be if we had kids who were not afraid to take risks, who were not afraid to think and who had a champion? Every child deserves a champion: an adult who will never give up on them, who understands the power of connections, and insists that they become the best that they can possibly be.” This is the type of community I value and I believe it is the one that you value as well. My hope is for each and every student at The Craig School to experience a strong sense of belonging, of community, and to experience what it is to have a champion. When we foster a positive school community, we remove another barrier to learning, allowing our students to truly shine.

Recently, I was reminded of a blog post from years past sharing lessons learned from the classic children’s story, The Little Engine That Could by Watty Piper, such as courage, strength, and a can-do attitude. The oft-recited words, “I think I can, I think I can…” to me, illustrate something even greater, self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is the belief in one’s ability to meet the challenges ahead and complete a task successfully. You may recall that as a result of an engine break down, a group of toys and dolls were left looking for a way to get up and over a mountain to reach the children on the other side. Many engines came and went, but alas, the Little Blue Engine, not as big nor as strong as other engines, came along and offered to help. At first, the Little Blue Engine wasn’t completely sure it would be able to do something that it had never done before. However, quickly this doubt changed and the Little Blue Engine started to think it really could climb the mountain. But it wasn’t only the Little Blue Engine’s belief in its ability that allowed it to get up and over the mountain to deliver the dolls and toys. The thought led to specific actions, “puff, puff, chug, chug;” actions that ultimately resulted in achieving the desired goal. Despite never making it up and over the mountain before, the Little Blue Engine began chanting, “I think I can,” until the task was accomplished. Through perseverance and resilience, the Little Blue Engine turned “I think I can” into “I thought I could.”

There is strong empirical support for the direct effects of self-efficacy and academic achievement. Just like The Little Blue Engine, students with learning disabilities may struggle with this construct. Many have experienced frustrations at school and for some these frustrations lead to the erroneous belief that they can not or will not find success in school. At The Craig School, I am continually awed by our faculty, who understand the strong, positive associations between efficacy, both individual and collective, and each student’s ability to achieve. This understanding is made evident daily in our classrooms as our teachers engage in instructional practices that foster self-efficacy among our students. While not exhaustive, these research-driven strategies include metacognitive awareness so that our students understand how they learn best, self-regulation, to enhance our students’ ability to set goals, make plans, and manage emotions to reach their desired outcome, and self-determination, so that our students learn how to make informed choices and manage their lives. A best practice in the field of special education is to equip students with the skills, attitudes, and opportunities to play an active, prominent role in their own learning. Fostering our students’ self-efficacy lays out a path to this end.

The Little Engine That Could presents an illustration of the belief in one’s ability to achieve. However, the story doesn’t end there. Look again at the toys and dolls in the broken engine. Together, they joined the Little Blue Engine in believing it could get over the mountain and deliver the toys to the children. This shared belief among the Little Blue Engine and the toys and dolls manifested into the action steps required to find success. At The Craig School, not only do we seek authentic opportunities to grow our students’ self-efficacy, we recognize that we must be active partners who also believe wholeheartedly in the ability of each and every one of our students to succeed and reach their full potential.

For more information on ways of giving or to make a donation online you can clicking here.